“Which is more important? The journey or the destination?” asked Big Panda

“The company.” said the Tiny Dragon

Backstory

In September 2021 (as a 33 year old), I moved to (South) Germany with my wife and son – and joined the then newly formed Computational Biology (‘gCBDS’ in short) Department of Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) as a ‘Senior Scientist’ (and ‘Product Owner’ afterwards for ~20 months). I was <20th hire of the department (incl. leadership team), which went on to hire >100 in a short space of time. So I didn’t get much of a chance to loiter and had to learn quickly to be helpful to the ‘new hires’. The Human Genetics team was an even newer team within gCBDS and designed to be a truly cross-cutting one – so we dealt with all therapeutic areas (there was six at the time: Cardio-Metabolic, Immunology & Respiratory, CNS, Cancer Immunology & Immunomodulation, Cancer Research, and Research Beyond Borders – which was ‘everything else’). It was very challenging at first – especially as there were colleagues who didn’t believe in the power of human genetics/omics in drug target ID/validation/repurposing – but gave me the chance to:

(i) meet colleagues who are experts in different fields and learn a lot about different diseases and their molecular causes/master mechanisms – and tweak my analysis pipelines and visualisations to their needs (published quiet a few papers with them too e.g. Jones et al., 2024; Kousathanas et al., 2024; Noyvert, Erzurumluoglu, Drichel, Omland & Andlauer et al., 2023; Qiu et al., 2024), and

(ii) lead (or co-lead) important initiatives such as the Digital Innovation Unit (DIU)’s Biobank Project where I would come up with ‘solutions’ as Product Owner (PO) to make the biobank data that BI invests heavily in more ‘accessible’ to the CompBio and wet-lab colleagues and ultimately impact the portfolio – pitching for funding to the leadership team (obtaining >450k euros in ~1.5 years), presenting ‘business value’ (e.g. making certain analysis pipelines >25% faster and cheaper, pushing targets to portfolio), scouting/interviewing CROs, and leading subteams/project managers as part of my PO role. We were also one of the earliest users of the UKB RAP (UK Biobank) and Sandbox (FinnGen) platforms, and helped shape the Our Future Health genotyping array. Having a bit of influence in the External Innovation camp also helped with bringing Dr Richard Allen – a leading scientist in the genetics of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (NB: BI has a blockbuster drug called Ofev used in treating IPF patients) – to Biberach for a week.

I am proud of what we were able to achieve and I probably wouldn’t be able to do most of these at this stage of my career if I was to stay in academia or had joined Pharma companies with more established CompBio/Human Genetics departments e.g. GSK, AZ, and Regeneron.

As a family, we learned, saw and grew a lot as individuals, so I wanted to jot down a few sentences to share our experiences for Comp. Biologists curious about a move to (South) Germany and/or Boehringer Ingelheim.

As always, happy to take any questions directly and/or in the comments section!

Looking back

I want to start with the ‘goodbye’ email I sent (with the above picture from ‘Big Panda and Tiny Dragon’) to my colleagues on my last day – which summarised my feelings:

Dear all,

I spent an action packed ~3 years as a fellow gCBDSer! Looking back, I not only learned so much as a scientist but also as a person. It would be too long to list the cultural, social, and emotional impact moving to Biberach/Germany had on me and my family, but we will never forget the teary eyes of many of our friends, neighbours, and Isaac’s kindergarden teachers/friends – we also shed a few tears to say the least. We enjoyed (almost!) every second of our time here and will be recommending BI as a great employer wherever we go. On this end, I thank Till (Andlauer) for contacting/encouraging me to join BI and the Human Genetics team – learned a lot from him.

I was fortunate enough to help shape the Human Genetics Team from its early days – most notably, championing Mendelian Randomisation to virtually all the therapeutic areas (TAs) – but also be Product Owner (PO) of the DIU’s Biobank project, where we* graduated three solutions to make the Biobank data FAIRer (via self-service tools/algorithms, and integration with NTC Studio) and more impactful. We pinpointed that at least 27 targets (across 5 TAs) that entered portfolio were significantly supported by this data in the ~1.5 years I was PO. I also want to underline that we helped with the deprioritisation of even more – which I believe can be as important as validating a target.

My family’s moved back to the UK last month as my wife started as a Lecturer at Warwick University and my son started school in Leicester. I will join a biotech after a little break (details will be shared on social media when I formally start).

If you’re ever in the UK, we would be very happy to host you and/or catch up over a kebab, fish & chips, or a curry – on me as usual 😉

Mach’s gut!

Mesut (on behalf of Fatma, Isaac & Newton)

*Too many people to thank but special thanks to Dr Boris Bartholdy, Dr Julio C. Bolivar-Lopez, Dr Johann de Jong, and Dr Hanati Tuoken – the Project Managers whom (co)led the solutions proposed to the DIU leadership team

Pros & Cons

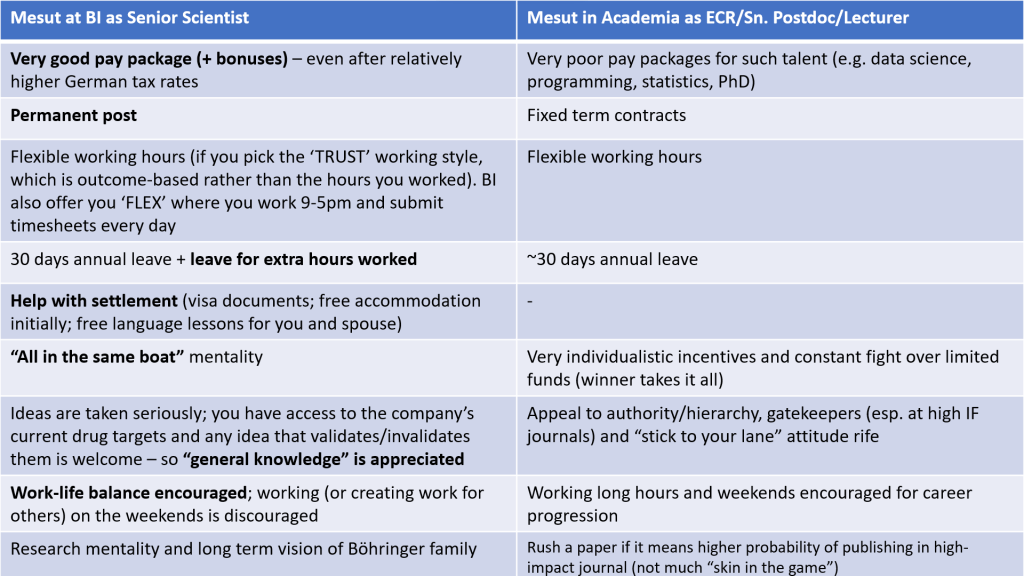

Going back to the beginning: It was not an easy decision to leave our ‘comfort zone’ in Leicester (where I lived most of my life; see blog post for details) but we couldn’t pass up the chance to move to a country like (the South of) Germany, learn a new culture/language, and meet lots of new people – in addition to working for a ‘Big Pharma’ company (see my blog post when I was about to join BI). We decided to live in Biberach an der Riss from ‘Day 1’ (when many colleagues suggested living in nearby Ulm – the birthplace of Einstein) – and this small town with a population of ~40k grew on us quickly. You’re left amazed at how clean, safe, and economically productive the town is with the presence of large companies such as Liebherr, Handtmann, KaVo, and Baur – in addition to BI’s largest research centre (with >6k employees) being located here.

Let me summarise the ‘Pros’ first:

1- BI pays well (and provides a lot of benefits) – even for German standards (which is higher than UK standards!). The company is also quiet special in that it’s the largest private pharma company in the world – so the way things work are bit different than other ‘Big Pharma’ companies. So you can certainly ‘learn and earn’ well here!

2- The German system supports families well e.g. child benefit/kindergeld is ~250 euros per child and the tax class is (usually) lower, and kindergartens (in South Germany) are of very good quality and cheap compared to the UK (at least Leicester!).

3- South Germany is beautiful with lots to do. It’s also at the heart of continental Europe, so flights are very cheap (check Ryanair flights from Memmingen Airport) and a lot of places (incl. Eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, Northern Italy, Czechia) are within driving-distance. There are also a lot of unique festivals (big and small) and fantastic Christmas Markets, which are worth attending at least once (see tweets below)

It’s not easy to pinpoint the challenges you personally might face at the Biberach site – as everyone’s context is different – but I’ll list the ones I personally struggled with (at least for some time):

Watch out for:

1- You’d need to learn a bit of German to get along with the older generation in South Germany – as they get annoyed if you talk English to them directly. Try learning at least basic German – then they also try to help and speak English with you if needed

2- Rent and living costs are high in Biberach (and Ulm). Thinking of buying a decent house? Better have a massive budget or forget about it! Housing market is even worse than the UK!

3- Do not argue with the police/government officials – or appeal their decisions (see ‘Anecdotes’ section below too). You will likely get double the fine with nowhere to complain. Things are a bit devoid of common sense when it comes to state matters. As an example from my own experience, an officer suddenly puts up a sign on our street to state that there’s no parking for a certain amount of time. But the sign that says ‘Residents only/free’ was still up there. So I had parked my car on my usual spot. I see the officer writing a ticket and go over to him to ask what was happening. He explains the situation and I apologise, show him the sign that confused me, also noting that I was new here. I assumed he hadn’t issued the ticket – but of course I was wrong. I then appealed the ticket to explain the situation (with photo evidence of the signs) but it was rejected – and this time with twice the fee. Another example: During the pandemic, my wife and son were made to queue outside for some time to let other passengers through. My (4 year old) son was about to burst and needed the toilet but the police didn’t allow him – no matter how many times she asked. This would almost never happen in the UK

4- Non-German take-aways/restaurants aren’t at the same level as the UK (at least nowhere near Leicester!). It can also get boring in the evenings and Sundays as most places are closed (see below to see what we were up to).

5- The turnover in BI’s CompBio department is high (a huge waste of resources unfortunately!), so get ready for many ‘welcomes’ and ‘goodbyes’. This is partially due to company/HR (e.g. miscommunication, false promises before joining, not allowed to live far from Biberach) and/or the leadership team-related issues (e.g. lack of empathy/care and/or power to keep ‘junior’ talent happy) but not always – and colleagues have cited a variety of other reasons (e.g. spouses struggling to find jobs, weather, not being able to integrate to South German society).

Why did I leave?

I resigned mostly due to family reasons – as my wife (who has a PhD in Law) was not able to find a job for >2 years in/near Biberach that also allowed hybrid or remote work. BI – which I believe will change for the better in this regard (but too late for me and family!) – doesn’t allow even Computational Biologists to live too far away from Biberach, which made it much harder for her as there were nice opportunities at international Law firms in/near Frankfurt and Berlin. Before I signed, we were reassured by an HR colleague that BI’s Legal Team should be able to find something but unfortunately not much came out of my wife’s endeavours. In addition to the disappointment regarding the lack of help from HR, Legal Team members, and my own boss(es) regarding my wife’s situation, I also wasn’t very happy with the direction of the team/department and – although I didn’t ‘downtool’ – it made it easier for me to leave my well-paying permanent position and look elsewhere.

Once my wife found a job at a prestigious university in the UK, I also looked around for UK-based posts that fit my skillset, ambitions and (were likely to have) met my minimum salary and flexibility expectations. After two rejections at the panel interview stage for senior roles (i.e. at Director and Assoc. Director level) at Big Pharma companies, and four strong applications not concluding due to

(i) cancellations (e.g. the interview process took >5 months in one application and the company/HR changed hiring priorities due to people leaving; another post was closed due to relocation to the US),

(ii) potential conflict of interest as they had signed recent contracts with BI or

(iii) ‘being overqualified’ and/or ‘being expensive’ (note that I wouldn’t have applied if I wasn’t happy with the title/role and/or salary), I decided to push different buttons and try to revive my data science/infrastructure business ‘data muse’ (datamuse.co.uk) – which I had initially set up with my sister (a successful businesswomen/data engineer) during the pandemic and then stepped down when I got hired by BI. I thought it was a good time for me to explore different sectors and it turned out to be a good decision (in the short term) as I widened my UK-based network and forged alliances with a Cambridge-based biotech (working as their Lead Comp. Biologist in ‘stealth mode’) and two SMEs (incl. a consultant role). However, I also had several applications progressing (incl. a Team Lead position at a very prestigious Aerospace company) and one biotech really ticked all the boxes for me: Bicycle Therapeutics – a biotech with fantastic potential (see their pipeline), nice culture/people, very good benefits and where I can learn a lot (e.g. had never worked with ‘bicycles’ before). I will (handover hands-on responsibilities at data muse and) formally start in January 2025.

Conclusion & Anecdotes

Long story short, I not only learned and travelled a lot (in Continental Europe, LA & South East Asia) but also earned/saved enough money during my ~3 years at Boehringer to (be in a position to) buy a house in a nice neighbourhood in my home town (i.e. Leicester). I also got to use the Agile/Atlassian Project and Team Management tools (e.g. Jira, Confluence), which I also utilised at data muse. As a family, we made many lifelong friends, which I see as the biggest gain.

I would certainly advise anyone to give BI at least a try should the right opportunity arise.

I want to finish with three (tragicomical) anecdotes – showing the good, the bad and the ugly side of ‘our journey’:

1- Although I was headhunted for the position at BI and had a very nice chat with Till Andlauer (1st hire and very senior member of the Human Genetics team – who persuaded me to apply), my initial application was rejected by HR. After two days of feeling betrayed (I was naïve at the time), I reached out to Till to ask why I was rejected and he told me there must have been a mistake. The same day HR writes back to say they made a mistake and I will be invited for a panel interview soon.

It was a good lesson on how ‘diligent’ and coordinated HR can be with some of these applications – and how much role luck (and making your own luck) can play!

2- For our arrival to Germany, our assistant had purchased a ticket to Munich airport from London. When we arrived, all the rental cars were gone (rent before arrival!). So we decided to ask for a taxi. When the taxi driver asked for >300 euros to travel to Biberach, I – still with the ‘Academia/Postdoc mindset’ (and not listening to my wife!) – decided that we would try the Deutsche Bahn/train (which cost ~40 euros). Normally, there would be 3 changes (Airport -> Munich -> Ulm -> Biberach) but we didn’t know/realise there were strikes that day (quite common!), so we ended up in Stuttgart rather than Ulm – which is further away. Took us >5 hours to get to Biberach! It was midnight when we arrived at the Biberach Bahnhof/Train Station and the first thing we see is 7-8 young adults having a serious fight with broken bottles being thrown about (we’ve lived there for 3 years since and never saw anything like it!). I was getting ready to defend my family in case they came close to us but thankfully we quickly found a taxi (driver who knew some English) who took us to our guest apartment. The apartment flat was a bit stuffy, so we opened the windows and (not exaggerating!) hundreds of mosquitos came in (we never had a mosquito problem in Leicester). I spent an hour killing them 😐

When I met my colleagues on my first workday, I asked how they (i.e. the cross-border hires) all travelled to Biberach and every single one said they used the taxi – as they knew the company would reimburse. You learn from these experiences I guess 😀

3- At the time of writing, Blue Card holders (which we were) are entitled to permanent residence in Germany in 27 months if they learn basic German (certified A1 or above) and pass the ‘Leben in Deutschland’ test. There was also a newly created ‘Highly-qualified worker’ visa (Sec 18c ResA), which does not specify any criteria on the website other than having ‘special expertise‘. Although we were planning to leave Germany due to my wife’s situation (no formal resignation yet), because we were very happy and wanted to keep in regular touch with our friends here (and even live here again if the right opportunity arose for both myself and my wife), I decided to go for this visa type – as I didn’t want to wait 4-5 months for a spot to enter the ‘Leben in Deutschland’ test in Biberach (I already had a A1 certificate with a ‘Sehr Gut’ grade from the Goethe Institute). I wrote a cover letter explaining why I wanted to apply and why I was qualified – enclosing my payslips, CV, Tax returns, proof of address, my son’s school details etc.

Turns out I was the first one to apply via this route in Biberach. Of course, this lack of clarity in the criteria created a big dilemma for the case worker and it took some time for her to do her research and get back to me. She then told me that I had to provide documentation that I would be able to sustain myself and family permanently (which is a huge criteria that she/her boss pulled out of thin air). I wasn’t going to reply initially (as I had now formally resigned from Boehringer and was returning to the UK in ~4 months) but later underlined what I wrote in the cover letter (e.g. highly-cited papers in the field, Top 2% earner in Germany, permanent contract) in a last bid to get a permanent visa – of course to no avail.

That was the end of it for me but not for her – and showed a side to German State affairs that we are not used to in the UK: Turns out she contacted BI to find out that I had now resigned and gave my name to the authorities to issue a fine to me (due to not informing the authorities of my resignation). I paid the fine but also wrote her the below email:

I received a letter today, titled ‘Anhorung im Bussgeldverfahren’ from the Biberach Bussgeldstelle. It seems like you told them that I did not inform you/Auslanderstelle regarding my resignation from Boehringer Ingelheim.

I am not sure why you decided to do this without telling me first – as I thought/understood that Boehringer Ingelheim would tell the authorities about my resignation. I hope you understand that I am not fully knowledgeable about the workings of this country – and it would have been kinder if you had informed/warned me first.

The big problem for me is that you treated me like I’m trying to stay here as an illegal immigrant. I am an established scientist whose CV includes highly-cited academic papers in some of the best journals. I was also chosen ‘top performer’ for consecutive years in my group at Boehringer Ingelheim. I had a permanent contract here and I decided to terminate it as we – as a family – found better opportunities in the UK.

You’ll be happy to hear that we are leaving Germany in a month’s time and will deregister as soon as possible.

Notable things about Biberach an der Riss:

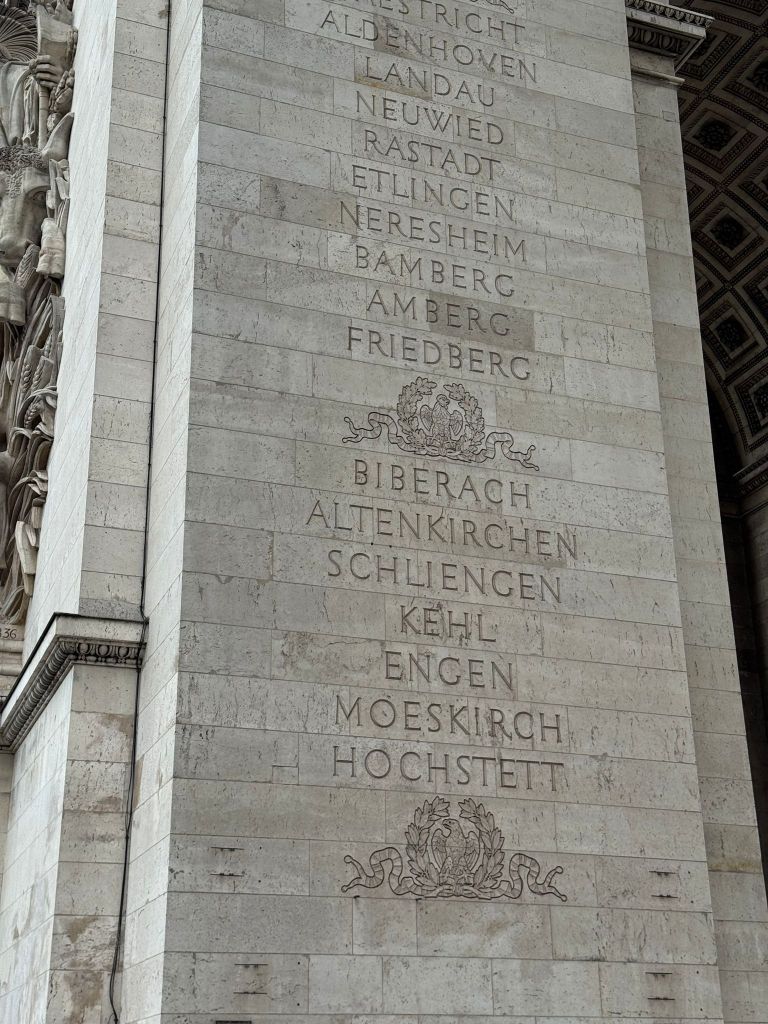

-Historical city: Imperial Free City (1281-1803), and battleground of the Thirty Years’ War (1618 -> +30?) & two Napoleonic wars (1796 & 1800 – see photo above)

-The Biberach Donkey (a story by the writer Christoph Martin Wieland; see summary here)

-Birthplace of Heinz H. Engler – who designed the first system tableware in the catering industry (Link)

-Birthplace of Loris Karius – Liverpool’s Goalkeeper in the 2018 Champions League Final (don’t watch the highlights!)

POIs closeby:

(Clustered POIs close to eachother)

-Burrenwald/Kletterwald

-Baltringen (Fossil site)

-Federsee/Wackelwald (Bouncy forest)

-Erwin Hymer (Caravan) Museum/Tannenbuhl/Bad Waldsee

-Öchslebahn

-Kürnbach Museum (watch out for special events)

-Jordanbad (we used to go to this spa almost every weekend with my son)

Nearby cities/POI to visit:

<1.5 hours driving distance:

-Ulm (Einstein’s birthplace, home of the Löwenmensch)

-Ravensburg (birthplace of the Ravensburger puzzles)

-Konstanz/Meersburg

-Lindau/Bregenz

-Breitachklamm/Oberstdorf

-Neuschwanstein Castle/Füssen

-Nördlingen

-Northern Switzerland: Schaffhausen (Rheinfall), Zürich, Basel

-Eastern France: Strasbourg, Colmar/Riquewihr

Related Tweets:

My comedy attempts – inspired by my interactions in Germany 🙂