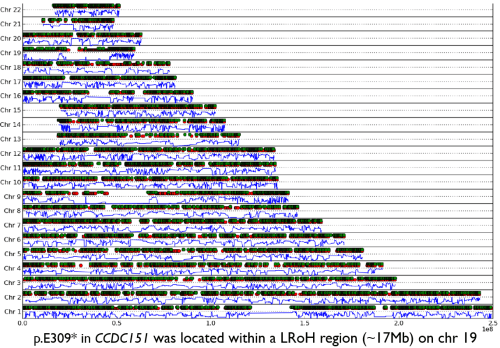

We – as a group – carried out the largest genome-wide association study to identify genetic variants that are associated with decreased lung function and increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. We hope that our findings will ultimately lead to the identification of effective drug targets for COPD. Image source: University of Leicester

I remember reading somewhere that ‘if you get asked the same question three times, then write a blog post about it’. That’s what I’ve been doing so far, and the purpose of this blog post is the same: to try and provide an answer to a commonly asked question. (Important note: my answers are in no way authoritative and only meant for interested non-scientists)

As a ‘Genetic Epidemiologist’, I constantly get asked what I do and what my (replace ‘my’ with ‘our’, as I do everything within a team) research can lead to. Please see my previous post ‘Searching for “Breathtaking” genes. Literally!‘ and My Research page for short answers to these questions. In tandem to these, I am constantly asked ‘why we can’t find a ‘cure’ for (noncommunicable) diseases that affect/will affect most of us such as obesity, diabetes, cancer, COPD – although there are many scientific advancements?’. I looked around for a straight forward example, but couldn’t find one (probably didn’t look hard enough!). So I decided to write my own.

I will first try and put the question into context: We do have ‘therapies’ and ‘preventive measures’ for most diseases and sometimes making that distinction from ‘a cure’ answers their question. For example, coronary heart disease (CHD) is a major cause of death both in the UK and worldwide (see NHS page for details) but we know how we can prevent many CHD cases (e.g. lowering cholesterol, stopping smoking, regular exercise) and treat CHD patients (e.g. statins, aspirin, ACE inhibitors). However, there are currently there are no ‘cures’ for CHD. So once a person is diagnosed with CHD, it is currently impossible to cure them from it, but doctors can offer quite a few options to make their life better.

I then gave it some thought about why finding a ‘cure’ was so hard for most diseases, and came up with the below analogy of a river/sea, water dam, and a nicely functioning village/city (excuse my awful drawing!).

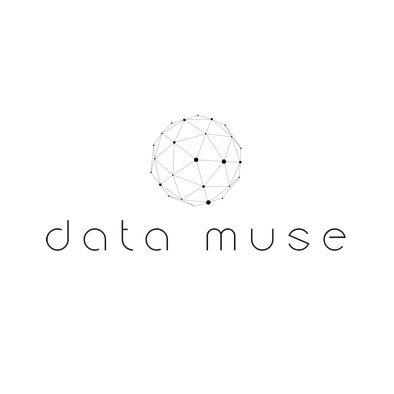

The first figure below sets the scene: there’s a water dam that’s keeping the river from flooding and damaging the nice village/city next to it. Now please read the caption of the below figure to make sense of how they’re related to a disease.

The river/sea is the combination of your genetic risk (e.g. you could have inherited genetic variants from your parents that increased your chances of type-2 diabetes) and environmental exposures (e.g. for type-2 diabetes, that would be being obese, eating high sugar content diet, smoking). The water dam is your immune system and/or mechanisms in your body which tame the sea of risk factors to ensure that everything in your body work fine (e.g. pancreatic islet cells have beta cells which produce insulin to lower your glucose levels back to normal levels – which would be damaging to the body’s organs if it stayed high).

So to ‘prevent’ a disease (well, flooding in this case), we could (i) make the water dam taller, (ii) make the dam stronger, and (iii) do regular checks to patch any damage done to the dam. To provide an example, for type-2 diabetes, point (i) could correspond to being ‘fit’ (or playing with your genes, which currently isn’t possible), point (ii) could correspond to staying ‘fit’, and point (iii) could correspond to having regular check-ups to see whether any preventive measures are necessary. Hope that made sense. If not, please stop reading immediately and look for other blog posts on the subject matter 🙂

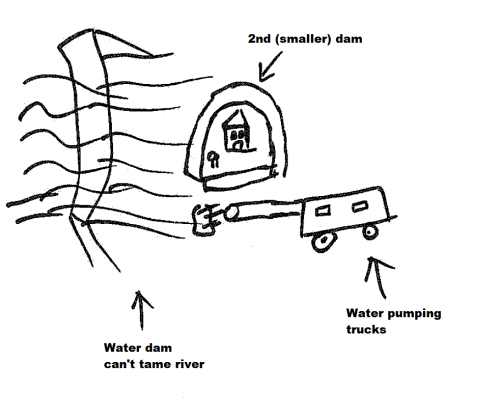

Using the figure below, I wanted to then move to ‘therapy’. So as you can see, the river has flooded i.e. this individual has the disease (e.g. type-2 diabetes as above). The water dam is now not doing a good job of stopping the river and the city is in danger of being destroyed. But we have treatments: (i) The (badly drawn) water pumping trucks suck up excess water, and (ii) we have now built a second (smaller) dam to protect the houses and/or slow the flow of the water. Again, to provide an example using type-2 diabetes, water pumping trucks could be analogous to insulin or metformin injections, and the smaller dams could be changing current diet to a ‘low sugar’ version. This way we can alleviate the effects of the current and future ‘floods’.

Analogy for therapy/treatment – after being diagnosed with the disease

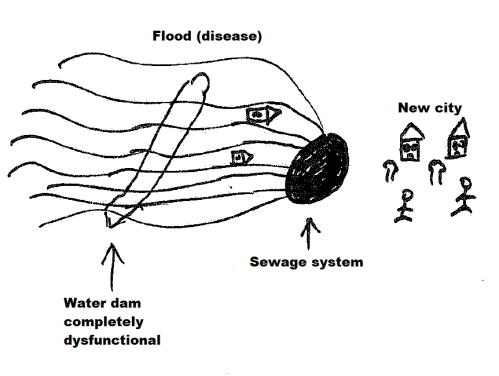

Finally, we move on to our main question: ‘the cure’. Using the same analogy as above, as the water dam is now dysfunctional, the only way to stop future ‘floods’ would be to design a sewage system that can mop up all water that could come towards the city. Of course the water dam and ‘old city’ was destroyed/damaged due to past floods, so we’d need to build a new functioning city to take over the job of the old one. A related real example (off the top of my head) could be to remove the damaged tissues and replace them with new ones. Genetic engineering (using CRISPR/Cas9) and/or stem cell techniques are likely to offer useful options in the future.

Analogy for cure – after being diagnosed with the disease

Hopefully it is now clear that the measures taken to prevent or treat the disease, cannot be used to cure the disease. E.g. you can build another dam in place of the old one, but the city is already destroyed so that’s not going to be of any use in curing the disease.

So to sum up, diseases like obesity, cancer, COPD are very complex diseases – in fact they’re called ‘complex diseases’ in the literature – and understanding their underlying biology is very hard (e.g. hundreds of genes and environmental exposures could combine to cause them). We’re currently identifying many causal variants but turning these findings into ‘cures’ is a challenge that we have not been able to crack yet. However, it is clear that the methods that we currently use to identify preventive measures and therapies cannot be used to identify cures.

I hope that was helpful. I’d be very happy to read your comments/suggestions and share credit with contributing scientists. Thanks for reading!