Source URL: PhD Comics

Figuratively speaking, what is the ‘worth’ of a certain academic? Between two academics, which one has had more positive academic impact than the other? How do you rank academics? And award grants, promotion, tenure etc. to the best* ones?

I’m not going to answer these questions but would like to chip in with some food for thought and suggestions.

Well; one may say: “It’s easy! Just compare their h-index and total no of citations!”

This may be an effective way to go about answering the question. Surely someone with an h-index of 30 has had more positive academic impact than someone with let’s say an h-index of 15 – and is the better candidate?

Maybe – that is if all things are equal regarding the way citations and the h-index works i.e. if both academics:

- are in similar fields – as papers in certain fields receive more citations overall than papers in other fields,

- are in similar stages in their careers – as comparing an early-career postdoc with an established “Prof.” wouldn’t be fair,

- have similar numbers of first/equal-first or last author papers – as an academic with many middle-authorships can have excessively inflated h-indexes,

- have similar number of co-authors – as it may be easier to be listed as a co-author in some fields than others and/or mean that more people will be presenting and citing the paper as their own, and

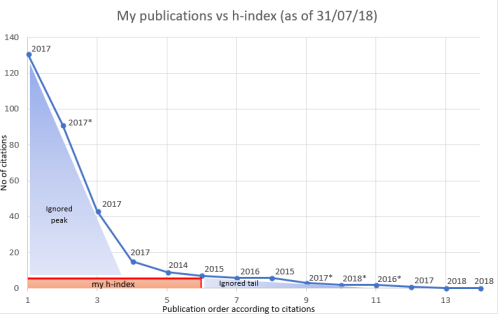

- have a similar distribution of citations across the papers – as the h-index ignores highly influential papers and the total citations can be highly influenced by even just one of these (see figure below).

I may have missed other factors, but I think these are the main ones (please add a comment below).

Calculating my h-index: Although problematic (discussed here), the h-index has become the standard metric when measuring the academic output of an academic. It is calculated by sorting the publications of an academic from most to least cited, then checking whether he/she has h papers with h citations e.g. if an academic has 10 papers with ≥10 citations but not 11 papers with ≥11 citations then their h-index will be 10. It was proposed as a way to summarise the number of publications that an academic has and their academic impact (via citations) with a single number. The above citation counts were obtained from my Google Scholar page

As of 31st July 2018, I have 14 published papers – including 5 as first/equal-first author – under my belt. I have a total citation count of 316 and an h-index of 6 (225 and 5 respectively, when excluding publications marked with an asterisk in the above figure). It is fair to say that these numbers are above average for a 29-year-old postdoc. But even I’m not content with my h-index – and many established academics are definitely right not to be. I’ll try and explain why: the figure above shows the citation distribution of my 14 publications sorted by the ‘number of times cited’ from the left (highest) to right (lowest). One can easily see that the h-index (red box) captures only a small portion of the general picture (effectively, 6 x 6 i.e. 36 citations) and ignores the peak (>6 on the y-axis) and tail (>6 on the x-axis) of the publication-citation distribution. I have also included the publication year of each paper and added an asterisk (*) against the publications where I haven’t provided much input e.g. I have done almost nothing for the Warren et al (2017) paper but it constitutes almost a third of my total citations (90/316)**. The ‘ignored peak’ contains three highly cited papers to which I have made significant contributions to and the ‘ignored tail’ contains research papers that (i) I am very proud of (e.g. Erzurumluoglu et al, 2015) or (ii) are just published – thus didn’t have the time to accumulate citations. What is entirely missing from this figure are my (i) non-peer-reviewed publications (e.g. reports, articles in general science magazines), (ii) correspondence/letters to editor (e.g. my reply to a Nature News article), (iii) blog posts where I review papers or explain concepts (e.g. journal clubs), (iv) shared code/analysis pipelines, (v) my PhD thesis with potentially important unpublished results, (vi) other things in my CV (e.g. peer-review reports, some blog posts) – which are all academia-related things I am very proud of. I have seen other people’s contributions in relation to these (e.g. Prof. Graham Coop’s blog) and thought that they were more useful than even some published papers in my field. These contributions should be incorporated into ‘academic output’ measures somehow.

It is also clear that “just compare their h-index and total no of citations!” isn’t going to be fair on academics that (i) do a lot of high-quality supervision at different levels (PhD, postdoc, masters, undergrad project – which all require different skill sets and arrangements), (ii) spend extra time to make their lectures inspiring and as educative as possible to undergrad and Masters students, (iii) present at a lot of conferences, (iv) do ‘admin work’ which benefits early-career researchers (e.g. workshops, discussion sessions), (v) do a lot of blogging to explain concepts, review papers, and offer personal views on field generally, (vi) have a lot of social media presence (e.g. to give examples from my field i.e. Genetic Epidemiology, academics such as Eric Topol, Daniel MacArthur, Sek Kathiresan take time out from their busy schedules to discuss, present and debate latest papers in their fields – which I find intellectually stimulating), (vii) give a lot of interviews (TV, online media, print media) to correct misconceptions, (viii) take part in public engagement events (incl. public talks), (ix) organise (inter-disciplinary) workshops, (x) inspire youngsters to become academics working for the benefit of humankind, (xi) publish reliable reports for the public and/or corporations to use, (x) provide pro bono consultation, (xi) take part in expert panels and try very hard to make the right decisions, (xii) engage in pro bono work, (xiii) do their best to change bad habits in the academic circles (e.g. by sharing code, advocating open access publications, standing up to unfair/bad decisions whether it affects them or not), (xiv) extensively peer-review papers, (xv) help everyone who asks for help and/or reply to emails… The list could go on but I think I’ll stop there…

I acknowledge that some of the above may indirectly help increase the h-index and total citations of an individual but I don’t think any of the above are valued as much as they should be per se by universities – and something needs to change. Academics should not be treated like ‘paper machines’ until the REF*** submission period, and then ‘cash cows’ that continually bring grant money until the next REF submission cycle starts. As a result, many academics have made ‘getting their names into as many papers as possible’ their main aim – it is especially easier for senior academics, many with a tonne of middle-authorships for which they have done virtually nothing****. This is not how science and scientists should work and universities are ultimately disrespecting the tax payers’ and donors’ money. Some of the above-mentioned factors are easier to quantify than others but thought should go into acknowledging work other than (i) published papers, (ii) grant money brought in, and maybe (iii) appearing on national TV channels.

Unless an academic publishes a ‘hot paper’ as first or corresponding author – which very few have the chance and/or luck to do – and he/she becomes very famous in their field, their rank is usually dictated by the h-index and/or total citations. In fact, many scientists who have very high h-indexes (e.g. because of many middle-author papers) put this figure at the top of their publication list to prove that they’re top scientists – and unfortunately, they contribute to the problem.

People have proposed that contributions of each author are explicitly stated on each paper but this is going to present a lot of work when analysing the academic output of tens of applicants – especially when the number of publications an individual has increases. Additionally, in papers with tens or even hundreds of authors, general statements such as “this author contributed to data analysis” are going to be assigned to many authors without explicitly stating what they did to be included as a co-author – thus the utility of this proposition could also be less than expected in reality.

It’s not going to solve all the problems, but I humbly propose that a figure such as the one above be provided by Google Scholar and/or similar bibliometric databases (e.g. SCOPUS, CrossRef, Microsoft Academic, Loop) for all academics, where the papers for which the respective academic is not the first author are marked with an asterisk. The asterisks could then be manually removed by the respective academic on publications where he/she has made significant contributions (i.e. equal-first, corresponding author, equal-last author or other prominent role) but wasn’t the first author. Metrics such as the h-index and total citations could then become better measures by giving funders/decision makers the chance to filter accordingly.

Thanks for reading. Please leave your comments below if you do not agree with anything or would like to make a suggestion.

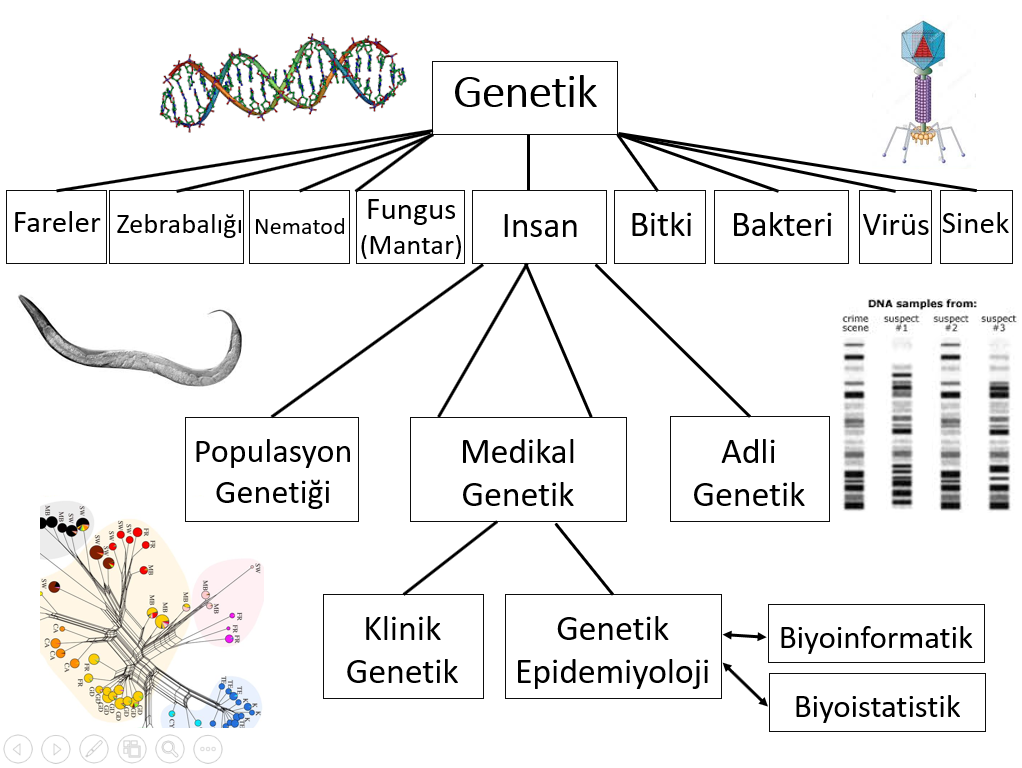

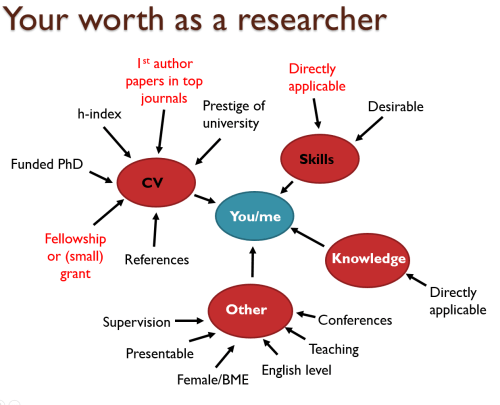

The heuristic that I think people use when calculating the worth of an early career researcher (but generally applies to all levels): ‘CV’ and ‘Skills’ are the two main contributors, with the factors highlighted in red carrying enormous weight in determining whether someone should get the job/fellowship or not. Virtually no one cares about anything that is outside what is written here – as mentioned in the post. Directly applicable: Some technical skill that the funder/Professor thinks is essential for the job; Prestige of university: where you did your PhD and/or undergrad; Funded PhD: whether your PhD was fully funded or not; Female/BME: being female and/or of BME background – this can be an advantage or a disadvantage depending on the regulations/characteristics of the university/panel, as underrepresented groups can be subjected to both positive and negative discrimination. NB: this is a simplified version and there are many factors that affect outcomes such as “who you know” and “being at the right place at the right time“.

Added on 30/10/18: I just came across ‘No, it’s not The Incentives—it’s you‘ by Tal Yarkoni about the common malpractices in academic circles, and I think it’s well worth a read.

*Making sure there’s a gender balance and that academics from BME backgrounds are not excluded from the process – as they’ve usually had to overcome more obstacles to reach the same heights.

**I have been honest about this in my applications and put this publication under “Other Publications” in my CV.

***REF stands for the ‘Research Excellence Framework’, and is the UK’s system for assessing the quality of research in higher education institutions. The last REF cycle finished in 2014 and the next one will finish in 2021 (every 7 years). Universities start planning for this 3-4 years before the submission dates and the ones ranked high in the list will receive tens of millions of pounds from the government. For example, University of Oxford (1st) received ~£150m and University of Bristol (8th) received ~£80m.

****Sometimes it’s not their fault; people add senior authors on their papers to increase their chances of getting them accepted. It’s then human nature that they’re not going to decline authorship. It sounds nice when one’s introduced in a conference etc. as having “published >100 papers with >10,000 citations” – when in reality they’ve not made significant (if any!) contributions to most of them.

PS: I also propose that acknowledgements at the bottom of papers and PhD theses be screened in some way. I’ve had colleagues who’ve helped me out a lot when learning some concepts who then moved on and did not have the chance to be a co-author on my papers. I have acknowledged them in my PhD thesis and would love to see my comments be helpful to these colleagues in some way when they apply for postdoc jobs or fellowships. Some of them did not publish many papers and acknowledgements like these could show that they not only have the ability to be of help (e.g. statistical, computational expertise), but are also easy to work with and want to help their peers.