This is a post inspired by a question I saw online: Which single public health intervention would be most effective in the UK?

I would like to share my own views on the question although don’t expect anything comprehensive as I don’t have much experience about how an idea can be taken further to impact policy and public health practice.

Something must be done – and fast!

Legend has it that a great chess player travelled to Manhattan to take part in a World Chess tournament. Looking around Central Park, he saw that a crowd had gathered around a street chess player who was offering money to those who could beat him. He decided to give it a go – and after a gruelling match, they shaked hands on a draw. This dented his confidence and ultimately caused him to return to his homeland without taking part in the tournament.

Little did he know that the street chess player was a grand master who wanted to pass time before taking part in the same the tournament.

What has this got to do with a public health intervention? I will come back to it…

From my observations over the last 7-8 years as a scientist studying different common diseases such as diabetes – to which £1 of every £10 of the NHS’s budget is spent on, obesity – which is the major risk factor for heart attacks, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – currently the third leading killer in the world, it is clear that cheap and effective treatments for these diseases are a long way away. This is not to say that there is no progress as there is tremendous research being carried out on (i) understanding the molecular causes of (e.g. genes, proteins that cause) these diseases and (ii) developing new therapies. The continuous economical costs of treating patients with current state-of-the-art therapies is reaching infeasible levels with a significant proportion being wasted on patients who do not adhere to their prescriptions properly1 and ‘top selling’ drugs being so inefficient that up to 25 patients need to be treated in order to prevent one adverse event such as a heart attack2. These diseases drain the NHS’s budget, cost the lives and healthy years of hundreds of thousands of people and causes emotional distress to the patients and their loved ones. If something is not done now – and quick – latter generations may not have an NHS that is ‘free and accessible to all’ to rely on as the system is already showing signs of failure in many parts of the country3,4 – although costing around 1 in 5 of the government’s annual budget.

Parents need help!

What is also striking about these diseases is that up to 9 in 10 cases are thought to be preventable. Thus, concentrating on prevention rather than ‘cure’ makes most sense as the only economically feasible solution lies here. No single public health intervention is going to solve all the problems that the UK health system faces currently but one thing that has always stared me in the face was how clueless and/or irresponsible most parents are, regardless of which socio-economic stratum they belong to – writing this sentence as I read an article on a teenager who died from obesity after his mother continually brought takeaway to his hospital bed5. The consequence is children living through many traumatic experiences, picking up bad habits and developing health problems due to a combination of ignorance, lack of guidance and toxic environments.

A wise man was once asked: “How do we educate our children?” and he is said to have replied “Educate yourself as they will imitate you”. As a new father, I got to observe first-hand that my child is virtually learning everything in life from myself and my wife. Thinking back, my parents never smoked, did not allow any visitors to smoke in the house, and kept me away from friends who smoked. Their actions were the main factor for myself and my three siblings to never start smoking – although there was pressure from my school friends. Research suggests that this is true across the general population, that is, if parents do not smoke, their children are more likely to become adults who will not either6; if parents prepare healthy food, their children will do too; if parents do not drink or drink moderately, the children will do too; if parents are educated, their children will be too7; and the list goes on… As the only economically feasible hope seems to be prevention, there is no better place to start than educating parents.

Since starting as a researcher at my current institute, I have been to a dozen or so ‘induction courses’, taking lessons on a variety of subjects from ‘equality and diversity’ to ‘fire safety’ to ’unconscious biases’. Although most seemed a bit of a time waster at first, after enrolling to them, I soon accepted that these were important as I did not know how crucial they were in certain situations – situations that are more common than one would think. I would not have attended them if they were not mandatory.

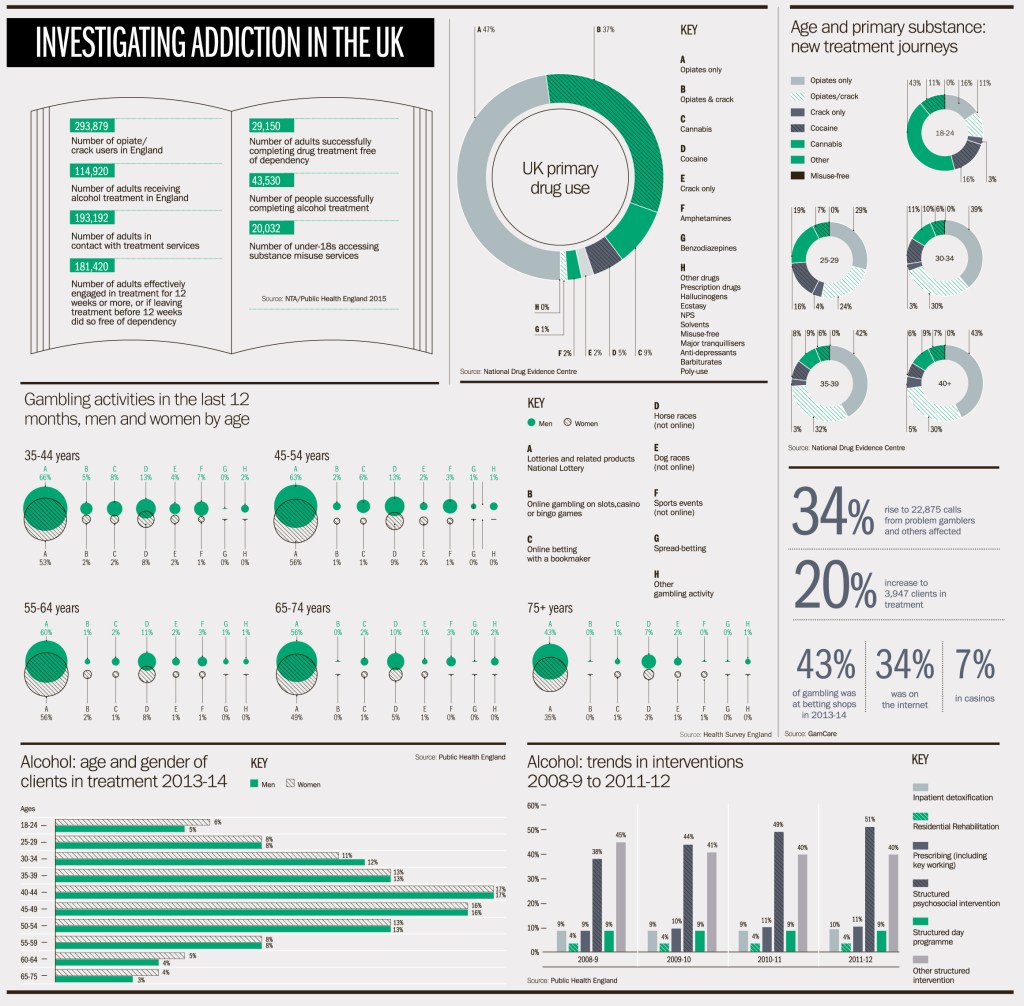

However, arguably, none of these skills that I picked up in these induction courses are as important as being a good parent and helping my children achieve their potential physically, intellectually, psychologically, emotionally and socially. I think it is irresponsible that there exists no mandatory training before people become parents. We as parents are expected to be not just people who keep our children alive by providing for them, but we are also expected to be good dieticians, sleep coaches, pedagogues, psychiatrists, life coaches, friends… Unsurprisingly, many parents are failing horribly as we are not equipped with a solid foundation to guide them properly. The result is: one-third of the population is obese, one-fourth drink above advised thresholds, one-fourth of students report to have taken drugs, one-fifth smoke (noting that vaping is not included in this figure), one-fifth show symptoms of anxiety or depression and up to one-tenth may be game addicts.

To help parents in this long and extremely difficult journey of parenthood, I propose mandatory courses tailored for first-time parents – with exemptions & alternatives available. The specific syllabus and the length of the course should be shaped by pedagogy, public health, psychology, sociology, and epidemiology experts but also by the parents themselves.

In this course parents can:

- Be persuaded about the importance of such a course – just as I learned that spending time learning about fire safety was not a bad idea

- Be provided with links on where to easily find reliable information (e.g. NHS website)

- Learn about the mental and physical health aspects of smoking, drinking alcohol, exercising, eating high sugar content food, pollution, watching TV, reading books, cooking healthy food, mould, asthma triggers, excessive use of social media etc.

- Feedback any problems they have to a central panel and make suggestions as to how the course could be improved

- Hear about local activities (e.g. ‘Stop smoking’ events, English courses, even events such as Yoga classes)

- Receive information about who they can contact if they themselves have addiction problems (e.g. smoking, alcohol, drugs, gambling)

- Learn about what to look out for in their children (e.g. any obvious signs of physical and mental diseases, bullying)

- Be encouraged to support their children achieve their potential – no matter what background they come from

- Be encouraged to offer help in local as well as national problems such as the organ donor shortage, climate change (recycling, carbon emissions), air pollution etc.

- Be reminded of the responsibility to provide future generations a sustainable world

- Be taught about the relevant laws (e.g. child seat, domestic abuse, cannot leave at home on their own).

I believe if the course is designed with the help of experts but also by parents, the course can be engaging and lead to more knowledgeable parents. This is turn will lead to positive changes in behaviour and a significant drop in the incidence of unhealthy diets/lifestyles, (at least heavy) smoking, substance use and binge drinking – major causes of the abovementioned common diseases. I think to ensure that parents engage and take part in the process, an exam should be administered where individuals who fail should re-take the exam. Parents who contribute to the process with feedback and suggestions can be rewarded with minor presents or a simple ‘thank you’ card from the government itself – a gesture that is bound to make parents feel part of a bigger process. Parents who are engaged in this process will also be encouraged to engage with their children’s education and help their teachers when they start going to school. Parental participation in turn, will positively affect academic achievement and the healthy development of children – a phenomenon shown by many studies8,9. Incentives such as additional child tax credit/benefit and/or paid parental leave for both parents should be considered to increase true participation rates.

These courses can then be accompanied by a number of optional courses where NGOs and volunteers from the local community can offer advice on matters such as ‘how to quit smoking?’, ‘how to find jobs?’, online parenting, English language courses (for non-speakers), and engaging children with local sports teams. I would certainly volunteer to give a session on the genetic causes of diabetes and obesity – and I know there are plenty of academics and professionals (e.g. experienced teachers, solicitors) out there whom would happily offer free advice to those who are interested. There are NGOs providing information on almost all diseases and health-related skills (e.g. CPR, first-aid) and this course would offer a more targeted and cost-efficient platform for them to disseminate their brochures and information on their upcoming events.

Many upper-middle to upper class parents regularly attend similar courses and events – and making this available to every parent would represent another way to close ‘the gap’10. Old problems persist but new ones are added on top such as online gaming, e-cigarettes, FOMO and betting addiction – and the courses can evolve with the times. A government which successfully implements such a course can leave a great legacy as social interventions have long lasting impact and even affect other countries.

One could argue that a course like this should be offered to every citizen at few key stages in their lives (e.g. first parenthood, before first child reaches puberty) – and that would be the ultimate aim. But as this option may initially be very costly and hard to organise and focusing on parents ensures that not only the parents are educated but consequently the children are too – making the process more cost efficient. The first courses could be trialled in certain regions of the country before going nation-wide.

We are all in the same boat – whether we realise or not

I would like to diverge a little to mention the potential sociological benefits of the proposed course: Tolstoy, in Anna Karenina wrote “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in their own way” – also an increasingly used aphorism in public health circles. However, I observe and believe that many of us are unhappy due to similar reasons: we all want to be listened to, understood and feel like we are being cared about. I believe the proposed course accompanied with an honest feedback system would be a great start in getting the ‘neglected masses’ involved in national issues.

I would like to finish by returning to the little story at the start. I believe that many parents, especially those from poorer backgrounds, give up trying for their children early on as they do not think that they or their children can compete against other ‘well-off’ individuals and therefore see no future for themselves. Their children and grandchildren also end up in this vicious cycle. But if they get to see first-hand in the proposed course that we all – rich and poor – start from not too dissimilar levels as parents and have the same anxieties about our children can also motivate us all to push a little bit extra and hopefully close the massive gaps that exist between the different socio-economic strata in the UK11 – and ultimately decrease the prevalence of the diseases that are crippling the NHS.

Further reading

- Shork, N. 2015. Personalized medicine: Time for one-person trials. Nature. 520(7549)

- Bluett et al., 2015. Impact of inadequate adherence on response to subcutaneously administered anti-tumour necrosis factor drugs: results from the Biologics in Rheumatoid Arthritis Genetics and Genomics Study Syndicate cohort. Rheumatology. 54(3):494-9

- NHS failure is inevitable – and it will shock those responsible into action. The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/06/nhs-failure-health-service. Accessed on 30th October 2019

- The first step towards fixing the UK’s health care system is admitting it’s broken. Quartz. https://qz.com/1201096/by-deifying-the-nhs-the-uk-will-never-fix-its-broken-health-care-system/. Accessed on 30th October 2019

- Teenager Dies from Obesity After Mother Brought Takeaways to His Hospital Bed – Extra.ie. URL: https://extra.ie/2019/09/12/news/extraordinary/child-dies-obesity-mum-hospital. Accessed on 27th October 2019

- Mike Vuolo and Jeremy Staff. 2013. Parent and Child Cigarette Use: A Longitudinal, Multigenerational Study. Pediatrics. 132(3): 568–577

- Sutherland et al. 2008. Like Parent, Like Child. Child Food and Beverage Choices During Role Playing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162(11): 1063–1069

- Sevcan Hakyemez-Paul, Paivi Pihlaja & Heikki Silvennoinen. 2018. Parental involvement in Finnish day care – what do early childhood educators say? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26:2, 258-273

- Jennifer Christofferson & Bradford Strand. 2016. Mandatory Parent Education Programs Can Create Positive Youth Sport Experiences. A Journal for Physical and Sport Educators. 29:6, 8-12

- How Obesity Relates to Socioeconomic Status. Population Reference Bureau. URL: https://www.prb.org/obesity-socioeconomic-status/. Accessed: 18/12/19

- Nancy E. Adler, Katherine Newman. 2002. Socioeconomic Disparities In Health: Pathways And Policies. Health Affairs. 21:2, 60-76