I believe that all scientists should be bloggers and that they should spare some thought and time to explain their research to interested non-scientists without using technical jargon. This is going to be my attempt at one; hopefully it’ll be a nice and short read.

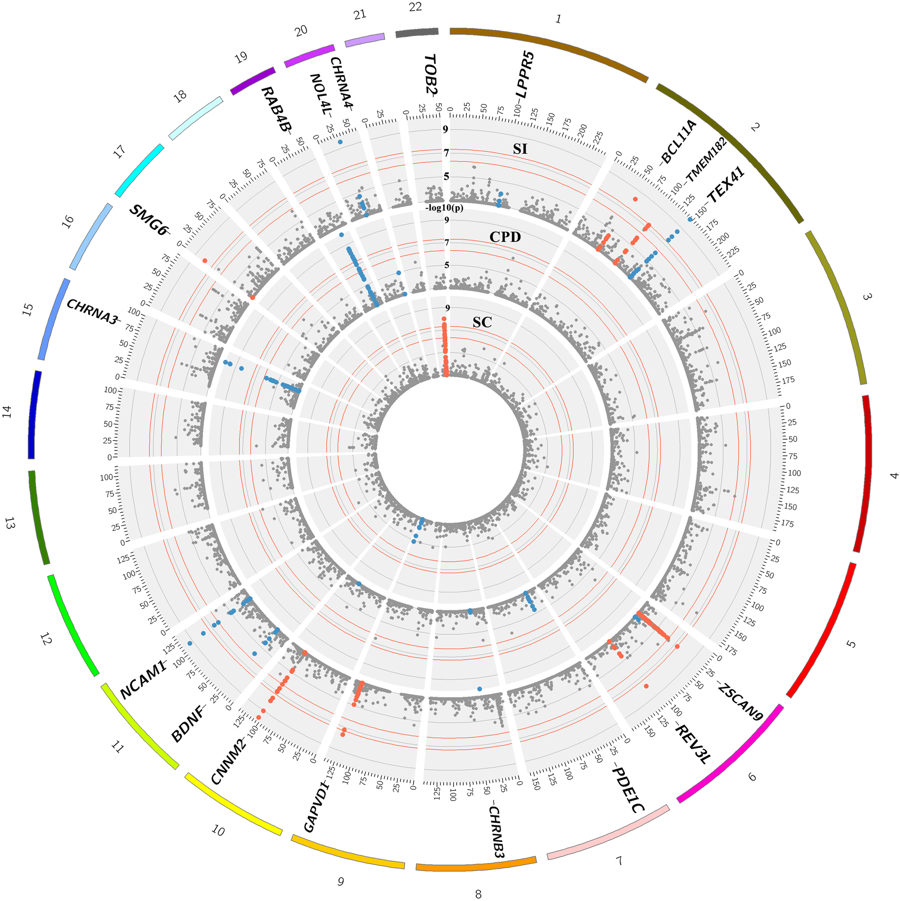

We’ve just published a paper in one of the top molecular psychiatry journals (well, named Molecular Psychiatry 🙂 ) where we tried to identify genetic variants that (directly or indirectly) affect (i) whether a person starts smoking or not, and once initiated, (ii) whether they smoke more. The paper is titled: Meta-analysis of up to 622,409 individuals identifies 40 novel smoking behaviour associated genetic loci. It is ‘open access’ so anyone with access to the internet can read the paper without paying a single penny.

If you can understand the paper, great! If not, I will now try my best to explain some of the key points of the paper:

Why is it important?

Smoking causes all sorts of diseases, including respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (which causes 1 in 20 of all deaths globally; more stats here) and lung cancer – which causes ~1 in 5 of all cancer deaths (more stats here). Therefore understanding what causes individuals to smoke is very important. A deeper understanding can help us develop therapies/interventions that help smokers to stop and have a massive impact on reducing the financial, health and emotional burden of smoking-related diseases.

Genes and Smoking? What!?

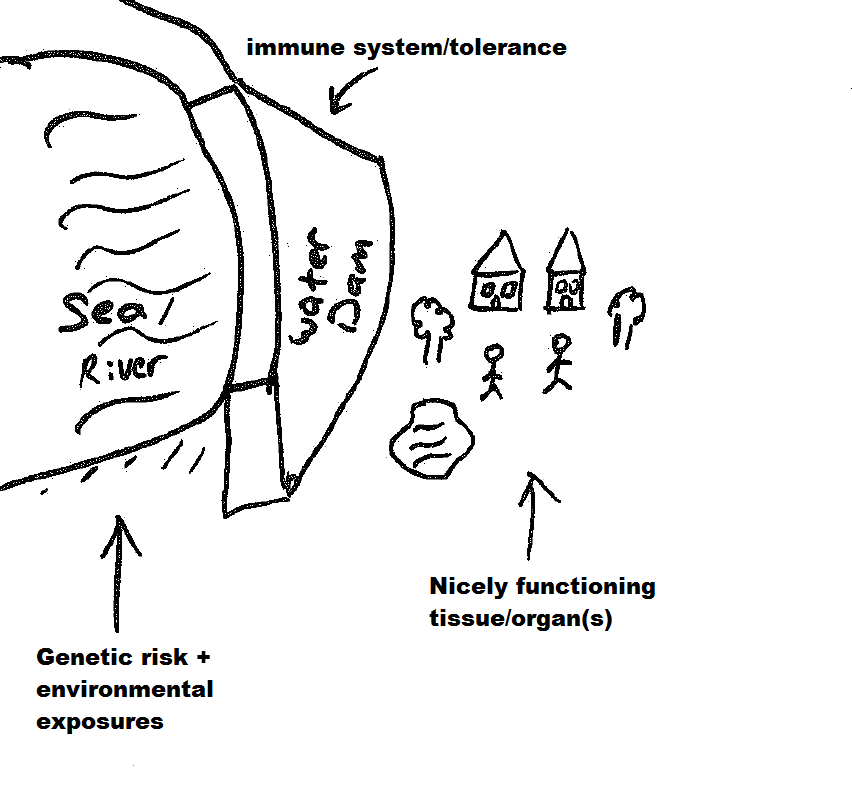

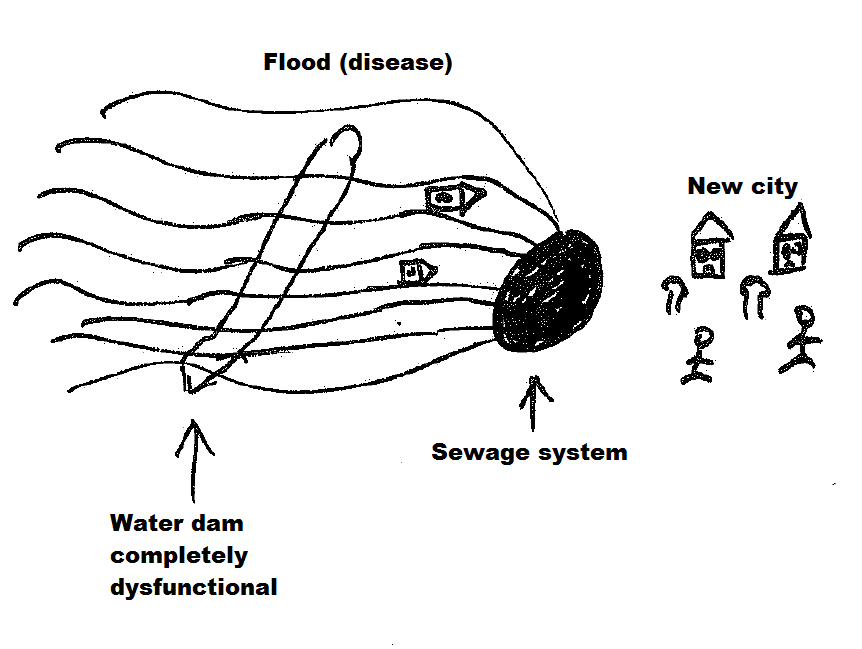

There are currently around fifty genetic variants that are identified to be associated with various smoking behaviours and we identified 40 of them in our latest study, including two on the X-chromosome which is potentially very interesting. There are probably hundreds more to be found*. So, it’s hard to comprehend but yes, our genes – given the environment – can affect whether we start smoking or not, and whether we’ll smoke heavier or not. This is not to say our genes determine whether we smoke or not so that we can’t do anything about it.

There are three main take-home messages:

1- I have to start by re-iterating the “given the environment” comment above. If there was no such thing as cigarettes or tobacco in the world, there would be no smoking. If none of our friends or family members smoked, we’re probably not going to smoke no matter what genetic variants we inherit. So the ‘environment’ you’re brought up in is by far the most important reason why you may start smoking.

2- I have to also underline the term “associated“. What we’re identifying are correlations so we don’t know whether these genetic variants are directly or indirectly affecting the smoking behaviour of individuals – bearing in mind that some might be statistical artefacts. Some of the genetic variants are more apparently related to smoking than others though: for example, variants in genes coding for nicotine receptors cause them to function less efficiently so more nicotine is needed to induce ‘that happy feeling‘ that smokers get. Other variants can directly or indirectly affect the educational attainment of an individual, which in turn can affect whether someone smokes or not. I’d highly recommend reading the ‘FAQ’ by the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (link below) which fantastically explains the caveats that comes with these types of genetic association studies.

3- Last but not least, there are many (I mean many!) non-smokers who have these genetic variants. I haven’t got any data on this but I’m almost 100% sure that all of us have at least one of these variants – but a large majority of people in the world (~80%) don’t smoke.

Closing remarks

To identify these genetic variants, we had to analyse the genetic data of over 620k people. To then identify which genes and biological pathways these variants may be affecting, we queried many genetic, biochemical and protein databases. We’ve been working on this study for over 2 years.

Finally, this study would not be possible (i) without the participants of over 60 studies, especially of UK Biobank – who’ve contributed ~400k of the total 622k, and (ii) without a huge scientific collaboration. The study was led by groups located at the University of Leicester, University of Cambridge, University of Minnesota and Penn State University – with contribution by researchers from >100 different institutions.

It will be interesting to see what, if any, impact these findings will have. We hope that there will be at least one gene within our paper that turns out to be a target for an effective smoking cessation drug.

Meta-analysis of up to 622,409 individuals identifies 40 novel smoking behaviour associated genetic loci – by Erzurumluoglu, Liu and Jackson et al https://t.co/vTxzjOPlpm

— A Mesut Erzurumluoğlu (@mesuturkiye) January 7, 2019

Further reading

1- FAQs about “Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a 1.1-million-person GWAS of educational attainment” – a must read in my opinion

2- Smoking ‘is down to your genes’ – a useful commentary on the NHS website on an older study

3- 9 reasons why many people started smoking in the past – a nice read

4- Genetics and Smoking – an academic paper, so quite technical

5- Causal Diagrams: Draw Your Assumptions Before Your Conclusions – a fantastic course on ‘Cause and Effect’ by Prof. Miguel Hernan at Harvard University

6- Searching for “Breathtaking” genes – my earlier blog post on genetic association studies

Data access

The full results can be downloaded from here

*in fact we know that there is another paper in press that has identified a lot more associations than we have