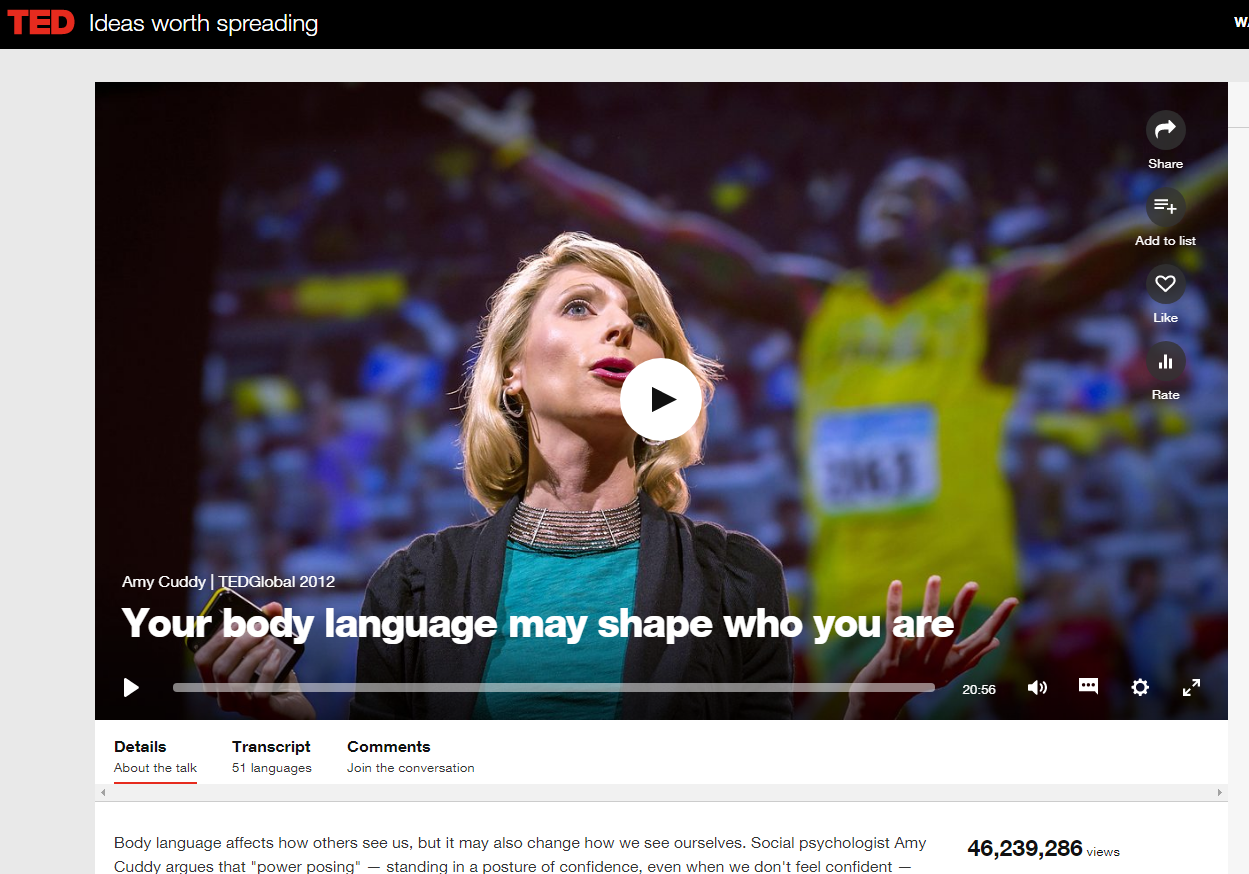

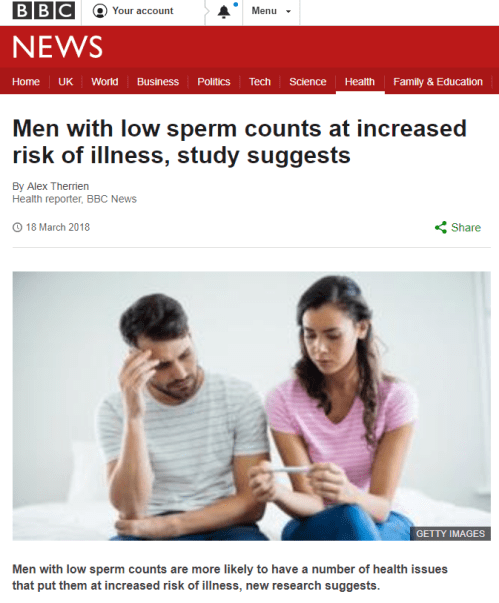

BBC news article published on the 18th March 2018. According to the article, men with low sperm counts are at a higher risk of disease/health problems. However, this is unlikely to be a causal relationship and more likely to be a spurious correlation. May even turn out to be the other way round due to “reverse causality”, a bias we encounter a lot in epidemiological studies. The following sounds more plausible (to me at least!): “Men with disease/health problems are likely to have low sperm counts” (likely cause: men with health problems tended to smoke more in general and this caused low sperm counts in those individuals).

As an enthusiastic genetic epidemiologist (keyword here: epidemiologist), I try to keep in touch with the latest developments in medicine and epidemiology. However, it is impossible to read all articles that come out as there is a lot of epidemiology and/or medicine papers published daily (in fact, too much!). For this reason, instead of reading the original academic papers (excluding papers in my specific field), I try to skim read from reputable news outlets such as the BBC, The Guardian and Medscape (mostly via Twitter). However, health news even in these respectable media outlets are full of wrong and/or oversensationalised titles: they either oversensationalise what the scientist has said or take the word of the scientist they contact – who are not infallible and can sometimes believe in their own hypotheses too much.

It wouldn’t harm us too much if the message of an astrophysics related publication is misinterpreted but we couldn’t say the same with health related news. Many people take these news articles as gospel truth and make lifestyle changes accordingly. Probably the best example for this is the Andrew Wakefield scandal in 1998 – where he claimed that the MMR vaccine caused autism and gastro-intestinal disease but later investigations showed that he had undeclared conflicts of interest and had faked most of the results (click here for a detailed article in the scandal). Many “anti-vaccination” (aka anti-vax) groups used his paper to strengthen their arguments and – although now retracted – the paper’s influence can still be felt today as many people, including my friends, do not allow their children to be vaccinated as they falsely think they might succumb to diseases like autism because of it.

The first thing we’re taught in our epidemiology course is “correlation does not mean causation.” However, a great deal of epidemiology papers published today report correlations (aka associations) without bringing in other lines of evidence to provide evidence for a causal relationship. Some of the “interesting ones” amongst these findings are then picked up by the media and we see a great deal of news articles with titles such as “coffee causes cancer” or “chocolate eaters are more successful in life”. There have been instances when I read the opposite in the same paper a couple of months later (example: wine drinking is protective/harmful for pregnant women). The problem isn’t caused only due to a lack of scientific method training on the media side, but also due to health scientists who are eager to make a name for themselves in the lay media without making sure that they have done everything they could to ensure that the message they’re giving is correct (e.g. triangulating using different methods). As a scientist who analyses a lot of genetic and phenotypic data, it is relatively easier for me to observe that the size of the data that we’re analysing has grown massively in the last 5-10 years. However, in general, we scientists haven’t been able to receive the computational and statistical training required to handle these ‘big data’. Today’s datasets are so massive that if we take the approach of “let’s analyse everything we got!”, we will find a tonne of correlations in our data whether they make sense or not.

To provide a simple example for illustrative purposes: let’s say that amongst the data we have in our hands, we also have each person’s coffee consumption and lung cancer diagnosis data. If we were to do a simple linear regression analysis between the two, we’d most probably find a positive correlation (i.e. increased coffee consumption means increased risk of lung cancer). 10 more scientists will identify the same correlation if they also get their hands on the same dataset; 3 of them will believe that the correlation is worthy of publication and submit a manuscript to a scientific journal; and one (other two are rejected) will make it past the “peer review” stage of the journal – and this will probably be picked up by a newspaper. Result: “coffee drinking causes lung cancer!”

However, there’s no causal relationship between coffee consumption and lung cancer (not that I know of anyway :D). The reason we find a positive correlation is because there is a third (confounding) factor that is associated with both of them: smoking. Since coffee drinkers smoke more in general and smoking causes lung cancer, if we do not control for smoking in our statistical model, we will find a correlation between coffee drinking and lung cancer. Unfortunately, it is not very easy to eliminate such spurious correlations, therefore health scientists must make sure they use several different methods to support their claims – and not try to publish everything they find (see “publish or perish” for an unfortunate pressure to publish more in scientific circles).

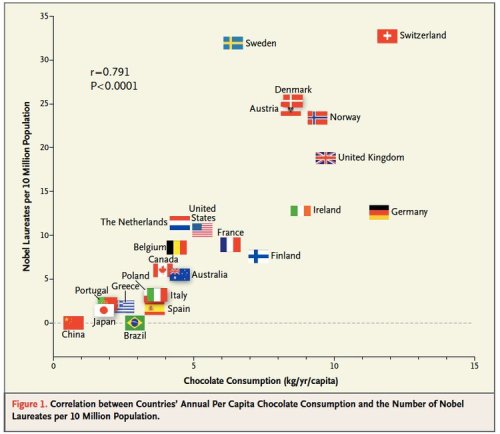

A figure showing the incredible correlation between countries’ annual per capita chocolate consumption and the number of Nobel laureates per 10 million population. Should we then give out chocolate in schools to ensure that the UK wins more Nobel prizes? However, this is likely not a causal relationship as it makes more sense that there is a (confounding) factor that is related to both of them: (most likely) GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. To view even quirkier correlations, I’d recommend this website (by Tyler Vigen). Image source: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMon1211064.

As a general rule, I keep repeating to friends: the more ‘interesting’ a ‘discovery’ sounds, the more likely it is to be false.

Hard to explain why I think like this but I’ll try: for a result to sound ‘interesting’ to me, it should be an unexpected finding as a result of a radical idea. There are just so many brilliant scientists today that finding unexpected things is becoming less and less likely – as almost every conceivable idea arises and is being tested in several groups around the world, especially in well researched areas such as cancer research. For this reason, the idea of a ‘discovery’ has changed from the days of Newtons and Einsteins. Today, ‘big discoveries’ (e.g. Mendel’s pea experimets, Einstein’s general relativity, Newton’s law of motion) have given way to incremental discoveries, which can be as valuable. So with each (well-designed) study, we’re getting closer and closer to cures/therapies or to a full understanding of underlying biology of diseases. There are still big discoveries made (e.g. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technique), but if they weren’t discovered by that respective group, they probably would have been discovered within a short space of time by another group as the discoverers built their research on a lot of other previously published papers. Before, elite scientists such as Newton and Einstein were generations ahead of their time and did most things on their own, but today, even the top scientists are probably not too ahead of a good postdoc as most science literature is out there for all to read in a timely manner (and more democratic compared to the not-so-distant past) and is advancing so fast that everyone is left behind – and we’re all dependent on each other to make discoveries. The days of lone wolves is virtually over as they will get left behind those who work in groups.

To conclude, without carefully reading the scientific paper that the newspaper article is referring to – hopefully they’ve included a link/citation at the bottom of the page! – or seeking what an impartial epidemiologist is saying about it, it’d be wise to take any health-related finding we read in newspapers with a pinch of salt as there are many things that can go wrong when looking for causal relationships – even scientists struggle to make the distinction between correlations and causal relationships.

Amy Cuddy’s very famous ‘Power posing’ talk, which was the most watched video on the TED website for some time. In short, she states that if you give powerful/dominant looking poses, this will induce hormonal changes which will make you confident and relieve stress. However, subsequent studies showed that her ‘finding’ could not be replicated and she that did not analyse her data in the manner expected of a scientist. If a respectable scientist had found such a result, they would have tried to replicate their results; at least would have followed it up with studies which bring other lines of concrete evidence. What does she do? Write a book about it by bringing in anecdotal evidence at best and give a TED talk as if it’s all proven – as becoming famous (by any means necessary) is the ultimate aim for many people; and many academics are no different. Details can be found here. TED talk URL: https://www.ted.com/talks/amy_cuddy_your_body_language_shapes_who_you_are

PS: For readers interested in reading a bit more, I’d like to add a few more sentences. We should apply the below four criteria – as much as we can – to any health news that we read:

(i) Is it evidence based? (e.g. supported by a clinical trial, different experiments) – homeopathy is a bad example in this regard as they’re not supported by clinical trials, hence the name “alternative medicine” (not saying they’re all ineffective and further research is always required but most are very likely to be);

(ii) Does it make sense epidemiologically? (e.g. the example mentioned above i.e. the correlation observed between coffee consumption and lung cancer due to smoking);

(iii) Does it make sense biologically? (e.g. if gene “X” causes eye cancer but the gene is only expressed in the pancreatic cells, then we’ve most probably found the wrong gene)

(iv) Does it make sense statistically? (e.g. was the correct data quality control protocol and statistical method used? See figure below for a data quality problem and how it can cause a spurious correlation in a simple linear regression analysis)

Wrong use of a statistical (linear regression) model. If we were to ignore the outlier data point at the top right of the plot, it becomes easy to see that there is no correlation between the two variables on the X and Y axes. However, since this outlier data point has been left in and a linear regression model has been used, the model identifies a positive correlation between the two variables – we would not have seen that this was a spurious correlation had we not visualised the data.

PPS: I’d recommend reading “Bad Science” by Ben Goldacre and/or “How to Read a Paper – The basics of evidence based medicine” by Trisha Greenhalgh – or if you’d like to read a much better article on this subject with a bit more technical jargon, have a look this highly influential paper by Prof. John Ioannidis: Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.

References:

Wakefield et al, 1998. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. The Lancet. URL: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2897%2911096-0/abstract

Editorial, 2011. Wakefield’s article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent. BMJ. URL: http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452