A farmer and his son had a beloved stallion who helped the family earn a living. One day, the horse ran away and their neighbours exclaimed, “Your horse ran away, what terrible luck!”

The farmer replied, “Maybe.”

A few days later, the horse returned home, leading a few wild mares back to the farm as well. The neighbours shouted out, “Your horse has returned, and brought several horses home with him. What great luck!”

The farmer replied, “Maybe.”

Later that week, the farmer’s son was trying to break one of the mares and she threw him to the ground, breaking his leg. The villagers cried, “Your son broke his leg, what terrible luck!”

The farmer replied, “Maybe.”

A few weeks later, soldiers from the national army marched through town, recruiting all the able-bodied boys for the army. They did not take the farmer’s son, still recovering from his injury. Friends shouted, “Your boy is spared, what tremendous luck!”

To which the farmer replied, “Maybe.”

IMPORTANT NOTE: EVERYTHING I WROTE BELOW ARE MY OPINIONS AND REFLECT MY EXPERIENCE IN ACADEMIA (IN THE UK) – AT THE TIME OF WRITING. THEREFORE, THEY PROBABLY WILL NOT APPLY TO YOU. ALSO, PLEASE READ FROM START TO FINISH (INCL. FOOTNOTES) BEFORE POSTING COMMENTS.

Very soon, I’ll be moving to the ‘Human Genetics’ team of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma (BI; Biberach R&D Centre in South Germany) as a ‘Senior Scientist’. I therefore wanted to look back at my time in academia and share my suggestion and concerns with other PhD students and early-career researchers (ECRs). Any criticism mentioned here is aimed at UK-based (research-intensive) academic institutions and “the system” – and not at any of my past supervisors/colleagues. The below are also going to be views that I have shared in some of my blog posts (e.g. Calculating the worth of an academic; Guide to an academic career in the UK; Bring back the ‘philosophy’ in ‘Natural philosophy’; What is success? YOU know better!) and with my colleagues throughout the years – and not something that I am just mentioning after securing a dream (will elaborate below on why I called it a ‘dream’) job at BI. (NB: See ‘Addendum (23/12/21)’ section, reflecting on my first 4-5 months at BI’s Human Genetics team)

To do my time in academia justice, I’ll get the good things out of the way first: I’ve been doing research for >10 years in UK-based academic institutions – first as a PhD student (Univ. of Bristol 2012-2015), then as a (Sn.) Postdoctoral Research Associate (2015-19 Univ. of Leicester; 2019-2021 Univ. of Cambridge) – and enjoyed almost every second of my time here. I met many world-class scientists but also great personalities whose memories and the things I learned from them will remain with me for the rest of my life. I was lucky to have had supervisors who also gave me the space and time to develop myself and I’d like to think I took good advantage of this. I also got to (i) publish quite a few papers I will always be proud about and (ii) travel to the US and many countries in Europe thanks to funding provided for academic conferences and, needless to say, none of them would have been possible without (4-year PhD) funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC UK) or support of my PhD/postdoc supervisors and colleagues. My time in the beautiful cities of Leicester (see: Life in Leicester), Bristol, and Cambridge was enjoyable too! I therefore would recommend any prospective scientist/researcher to spend at least some time as a ‘Postdoc’ in a research intensive UK-based university.

On top of all this, if you were to ask me 5 years ago, I would have said “I see myself staying in academia for the rest of my life” as I viewed my job as being paid for doing a ‘hobby’ – which was doing research, constantly learning, and rubbing shoulders with brilliant scientists. However, things started to change when I became a father towards the end of 2018, and I slowly began to have a change of heart about working in academia due to the well-known problems of fixed-term contracts/lack of permanent job opportunities, relatively poor* salaries compared to the private sector, and the many hurdles (incl. high workload) you need to overcome if you want to move a tiny bit up the ladder. The only thing keeping me going was my ideals of producing impactful science, my colleagues, and the possibility of pursuing my own ideas (and having PhD students). No one needs my acknowledgement to learn that there is ‘cutting-edge’ and potentially very impactful science being done at universities but the meaning of ‘impact’ for me changed during the COVID-19 pandemic when I was sat at home working on projects which I felt didn’t have much immediate impact and probably will not have much impact in the future either – and if they did, I probably would not be involved in the process as an ECR. On top of this, many of the (mostly COVID-19, and academia-related) analyses I was sharing on my Twitter page and blog were being read by tens of thousands. I was also heavily involved with the crowdfunding campaign of a one-year-old spinal muscular atrophy (type-1) patient (see tweet and news article). And these were both eye-opening and thought provoking! So the problems that I ignored or brushed under the carpet when I was a single, very early-career researcher were suddenly too big to ignore, and enduring through fixed-term jobs, relatively low pay packages* and a steep hierarchy (i.e. much more ‘status’ oriented than ideal) was just not worth it.

One of my biggest disappointments was not being able to move to Cambridge with my family because (i) Cambridge is very expensive relative to Leicester, and (ii) Univ. of Cambridge doesn’t pay their ECRs accordingly – mind you, I was being paid the equivalent of a (starting) ‘Lecturer’ post at the University’s pay scales (Point 49; see ‘Single Salary Spine’), so many of my colleagues were being paid less than myself.

There was also the issue of not having enough ‘independence’ as an ECR to work on different projects that excited me. As a ‘postdoc’, my priority had to be my supervisor’s projects/ideas. If I wanted to pursue my own projects, I had to bring my own salary via fellowship/grant applications – even those would have to be tailored towards the priorities of the funding bodies. Applying for grants/fellowships is not something I like or I’m trained for but I did try… I submitted three (one grant and two fellowship) applications and made it to the interview/final stage every time, however they were all ultimately rejected mostly because I “was not an expert on that respective disease” or “was too ambitious/couldn’t do all these in 3 (or 5) years”. I guess I also laid all my cards on the table and didn’t hide the fact that I was a proud ‘generalist’** and was never going to be a specialist as I am just too curious (and unwilling) to be working on a single disease or method. In addition to these, I had also co-applied (with a Lecturer colleague in the Arts dept. where we had to submit quite a few documents and a short video) for a very small grant (of ~£6000) to organise a conference to discuss the problems of asylum seekers/refugees in the UK, but it was rejected for strange reasons. I acknowledge that there is an element of luck involved and on another day with another panel, I may have been awarded but these rejections were also eye openers. (NB: I believe the ‘all-or-nothing’ nature of fellowship/grant applications should be revised as a colossal amount of researchers’ time and effort – and therefore taxpayers’ money – is being wasted)

But – in line with the story (of the Chinese farmer) I shared at the start – I am now happy that they didn’t work out as it probably would have meant I stayed in academia for longer (i.e. until the end of my fellowship period). I always took the ‘doing my best and not worrying about the outcome‘ approach and this has proven to be a good strategy for me so far.

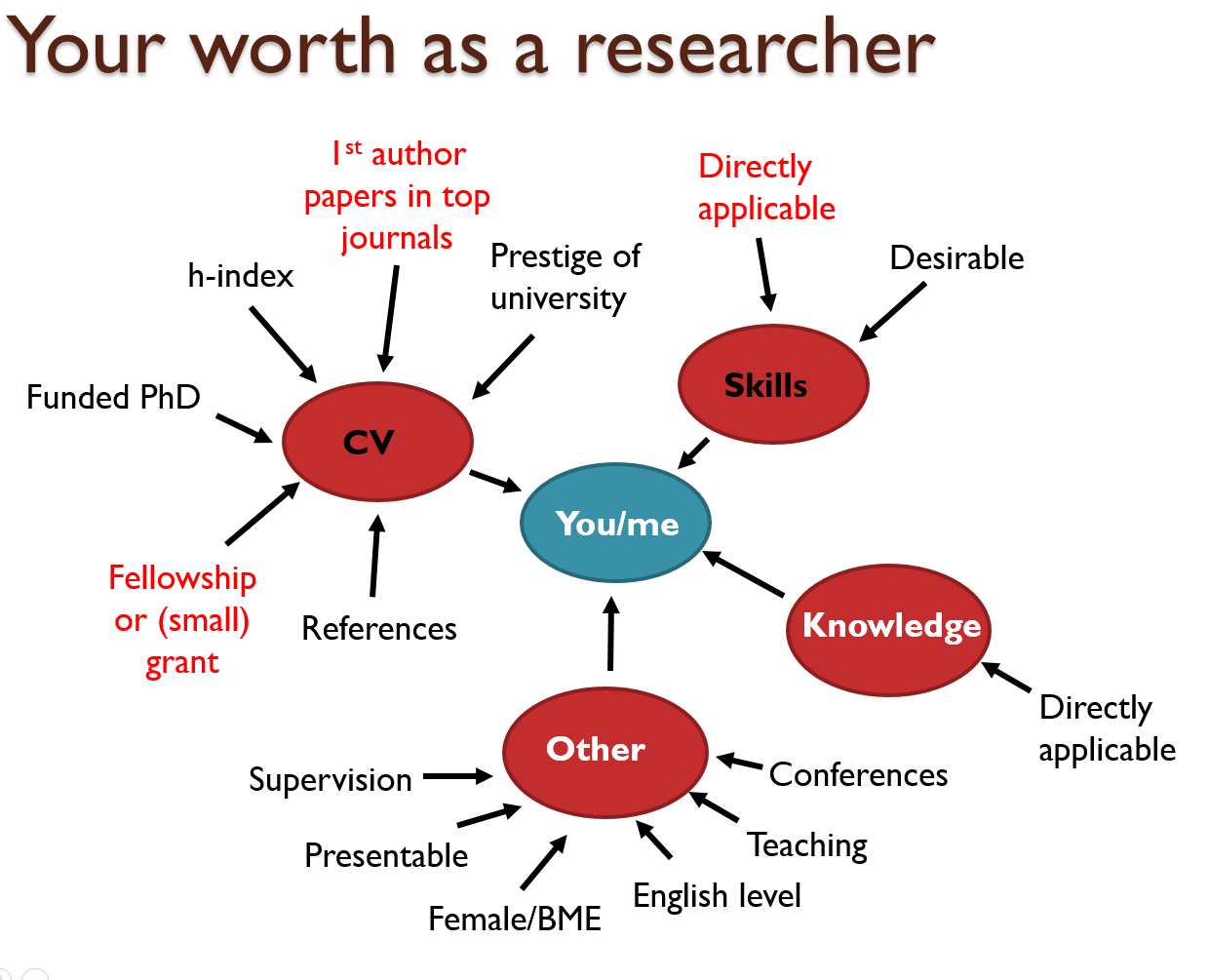

Although unhappy with the way ‘the system’ took advantage of ECRs, I did try and “play by rules” to ramp up my CV and network by applying to become a ‘Non-stipendiary Junior Research Fellow’ at one of the colleges of the Univ. of Cambridge to increase my chances of securing a permanent lecturer post at a high-calibre university. Although I enjoy teaching and think I am good at explaining concepts, the main reason for applying was to add more teaching experience in my CV and secondly, to be more involved with the community of students and ECRs in Cambridge – which I did not have a chance to do much, mostly as I and my wife decided not to move to Cambridge from Leicester for the reasons mentioned above (underneath the first figure). I made a solid application and got to the interview stage. I thought the interview panel would be delighted to see someone like me who has a relatively good academic CV for an ECR (see my CV) but also does sports, has his own podcast, who tried to be active on social media (I had more followers than the college on Twitter – although they’re very active), who writes highly read blogs (some of my blog posts are read and shared by tens of thousands), led many student groups (incl. the President of Turkish Society at the Univ. of Bristol and Leicester) etc. to join their ‘guild’ but I was very surprised to receive a rejection email a couple of weeks later. I was going to work there for free, but it seems like they didn’t value my skills at all and that there were at least 5 other people who they thought were going to contribute to the College’s environment more than me. This was another eye-opener: Academia is full of (highly talented) ECRs who are just happy to do things for free for the sake of adding stuff to their CV and I realised I was about to do the same. I remember thinking “I dodged a bullet there” – I decided it just wasn’t worth fighting/competing over these things. I knew now that I had to explore options outside of academia more assertively as I could see clearer that universities and the senior members who helped build this system were just taking advantage of ECRs’ idealism and ambitions but also desperation. (BTW: I find it astonishing that non-stipendiary fellowships in Cambridge are even a thing. They state that they don’t expect much from their fellows but they clearly do)

I then shared a 1-page CV in certain job recruitment sites to see what was out there for me and I was surprised to see how valuable* some of my transferable skills were to businesses in different sectors. I had many interviews and pre-interview chats with agents and potential employers (incl. Pharma, other private sectors, and public sector) in the last 6 months but only one ticked all the boxes for me: this ‘Senior scientist’ role at the Human Genetics team of BI – who valued my versatility and expertise in various fields***. Thus, I took time out to fully concentrate on the process and prepared well. I had to go through five interview stages, including an hour-long presentation to a group of experts from different fields, before I was offered the post. Throughout the process I also saw that many of my prospective colleagues at BI had seen the abovementioned problems earlier than I did and made the move. They were all very happy, with many working, and hoping to stay, in the company for a long time. I should also mention I had a Lecturer job lined up at the Univ. of Manchester**** too but the opportunity to work for BI’s ‘Human Genetics’ team was too good to refuse.

I didn’t mean this post to be this long so I’ll stop here. To sum up, I am proud of the things I’ve achieved and the friends I’ve made along the way – and if I was to go back, I wouldn’t change anything – but I believe it is the right time for me to leave academia. I think I’ve been a good servant to the groups I worked in and tried to give all I could. Simultaneously, I grew a lot as a scientist but also as a person – and this was almost all down to the environment we were provided at the universities I worked in. But having reached this stage in my life and career, I now think that (UK) universities don’t treat us (i.e. ECRs) in the right way and provide us with the necessary tools or the empathy to take the next step. I don’t see this changing in the near future either because of the fierce job market. Universities are somehow getting away with it – at least for now. This is not to say other sectors are too different in general but I would strongly recommend exploring the job market outside of academia. You may stumble on a recruiter like BI and a post like the one I have been offered, which matches my skill set and ambitions but also pay well so I can live a decent life with my family – without having to live tens of miles away from my office.

Let me re-iterate before I finish: What I wrote above will most probably not apply to you as I (i) am a UK-based academic/researcher, (ii) am an early-career researcher in a field which also has a strong computational/programming and statistics component – so I have a lot of easy-to-sell transferable skills to the Pharma companies/private sector, (iii) am a ‘generalist’** rather than a ‘specialist’ – so I’m a person major funding bodies currently aren’t really too keen on, (iv) don’t have rich parents or much savings, and am married (to a PhD student) and have a son to look after – and thus, salary*****, living in a decent house/neighbourhood and spending time with my family is an important issue, and (v) am an impatient idealist, who wants to see his research have impact – and as soon as possible. I am also in a position that I can make a move to another country with my family.

Footnotes:

*Contractor jobs usually offer much better pay packages than permanent jobs in the ‘data science’ field e.g. as soon I as put my CV on the market as a ‘health data scientist’, I got contacted by a lot of agents who could find me short-term (3-12 months mainly) contracts with very good pay packages. Just to give one example of the salaries offered, there was one agent who in an apologetic tone said: “I know this is not very good for someone like you but we currently offer £400 a day to our contractors but I can push it to £450 for you.” – this is ~3x the daily rate of my salary at the Univ. of Cambridge!

**I’ve always been involved in top groups and ‘cutting-edge’ projects so the jump from academia to Pharma in terms of research quality is not going to be too steep but the possibility of being directly involved in the process of a drug target that we identify go through the stages and maybe even become a drug that’s served to patients is not there for a (32 year old) ECR in academia – maybe, when I’m 45-50 years old. I also like the “skin in the game” and “all in the same boat” mentality in many Pharma/BI posts, which I do not see in academia. The current system incentivises people to be very individualistic in academia; and the repetitive and long process of publishing (at least partially) ‘rushed’ papers to lay claim to a potential discovery are things that have always bothered me. I don’t see how I can further improve myself personally and as a scientist as I don’t think my skills were anywhere near fully appreciated there – the system almost solely cares about publishing more and more papers, and bringing in funding. I have many ‘junior’ and ‘senior’ friends/colleagues who have made the transition from academia to Pharma (incl. Roche, NovoNordisk, GSK, AZ, Pfizer) and virtually all of them are happy to have moved on.

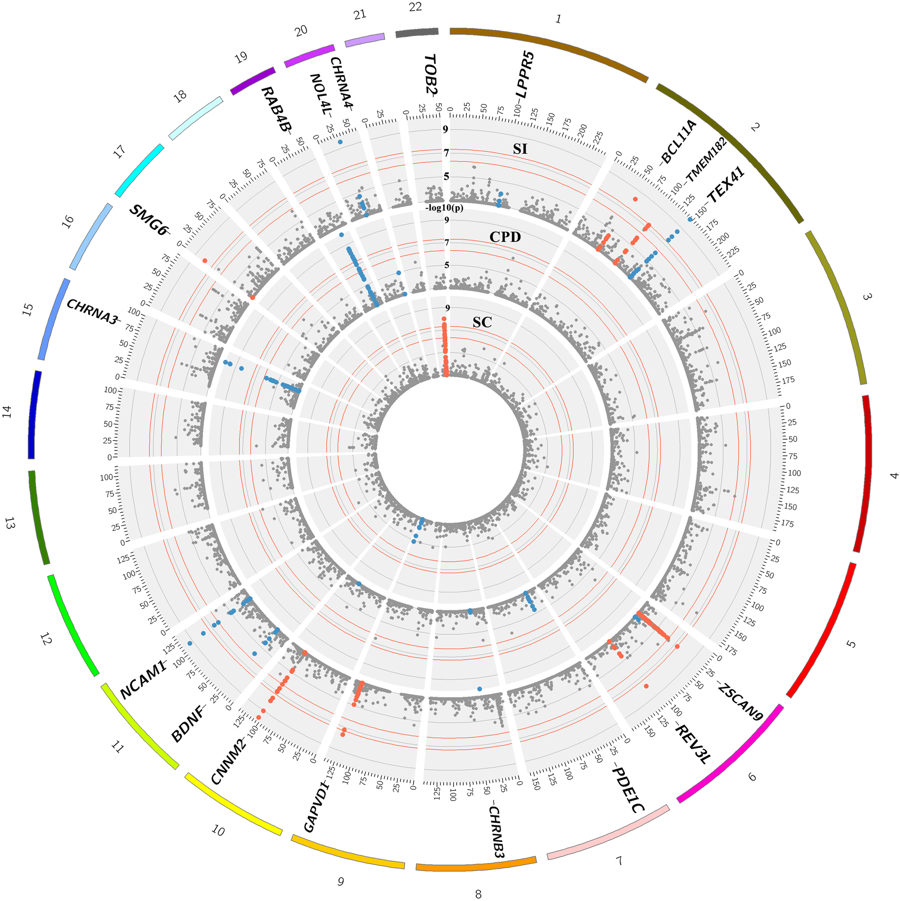

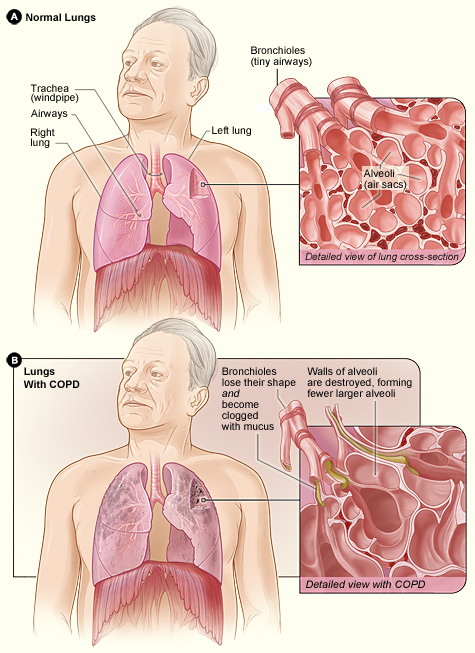

***As you can also see from my Google Scholar profile (and CV), I have worked on different diseases/traits and concepts/methods within the fields of medical genetics (e.g. rare diseases such as primary ciliary dyskinesia and Papillon-Lefevre syndrome), genetic epidemiology (e.g. common diseases such as type-2 diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and related traits such as smoking behaviour and blood pressure), (pure) epidemiology (COVID-19 studies), population genetics (Y-DNA & mtDNA haplogroup studies), and statistical genetics (e.g. LD Hub, HAPRAP) – and this is generally not seen as a ‘good sign’ (even when I’ve published papers in some of the most respectable journals in the respective fields as first/equal-first/prominent author) by some ‘senior academics’ (who review your grant/fellowship applications, and papers submitted to respectable journals) as many have spent their entire careers on a single disease, and sometimes on a single/few genes. It doesn’t mean they are right, but they usually make the final decision – and some like to act as gate keepers.

****I applied to the Univ. of Manchester post in case I would not get the BI job but also because it was a nice opportunity to work at a top university/department with high quality students and great scientists. They were also happy to pay me at the higher end of the ‘Lecturer’ salary scale. I believe I would have been a good lecturer and colleague but I just did not see myself in (UK) academia in its current state.

*****Although I – with my wife and son – was living in a nice neighbourhood and house in Leicester (renting of course!), due to my son’s expenses incl. a private nanny for a couple of days a week as my wife was also busy like me (small matter of writing her PhD thesis!), we were basically living paycheck to paycheck – and that was hard. When there were unexpected expenses, we used my wife’s (small amount of) savings, then asked my brother to help out financially – and that was hard too. It was almost impossible to fully concentrate on my research as I was always on the lookout for investment opportunities using the small amount of money I had on the side. At one point, I even contemplated doing casual work to earn a bit of cash on the side. Needless to say, I am very disappointed with the pay packages in academia – at least a stratified approach according to field, (transferable) skillset, and marriage/child status/other circumstances should be considered in my opinion. I also think, universities should at least provide guidance on solid investment (incl. mortgage) opportunities to their ECRs, so they can potentially earn or save a bit more. I can’t say much about my salary but it is a senior and permanent post, and my pay package also includes many of the perks of academia (e.g. >30 days of paid annual leave, flexible working hours, conference/travel allowance).

Couple of tweets – in addition to the blog posts I shared above – where I complain openly about the state of (UK-based) academia:

1- I don’t know how “no/limited feedback” has been normalised in academia:

2- I think science communication is as important as the papers we publish:

3- Publishing papers for the sake of publishing and inflating h-indexes:

Addendum (23/12/21) – Reflecting on my first 4 months at BI’s Human Genetics team:

I was going to write a piece later but decided to add to this post now as I have been/am being invited to many ‘academia v industry/pharma‘ workshops/talks and saw that there is a lot of interest in this subject. I cannot properly respond to all emails or accept all invitations, thus would like to direct people here when needed…

A quick summary of what I’m doing: I’m a ‘Senior Scientist’ in the relatively newly established Human Genetics team of BI – and we’re located at the International Research Centre in the beautiful city of Biberach an der Riss in South Germany. As the Human Genetics team, we’re currently building analysis pipelines to make use of the huge amount of human genetics, proteomics and transcriptomics data that’s available to (in)validate the company’s portfolio of drugs (see below video for details).

If I say a few words about BI – which I didn’t know before I joined: BI one of the largest family-owned companies in the world with >20 billion euros revenue per year and >50k employees all around the world of which >8k are researchers (largest R&D centre is in Biberach an der Riss, where we’re also located) – so the company and the Boehringer/Von Baumbach family value R&D a lot. Some family members also attend research days organised within the company – which I find very encouraging as an employee but also a scientist at heart!

The other exciting thing for me is that the company’s currently going through a phase of massive expansion in ‘data driven drug target validation’, so the Comp. Bio/Human Genetics department is getting a lot of investment and are going to hire a lot of people in the near future – and I’m very happy to be involved in this process too.

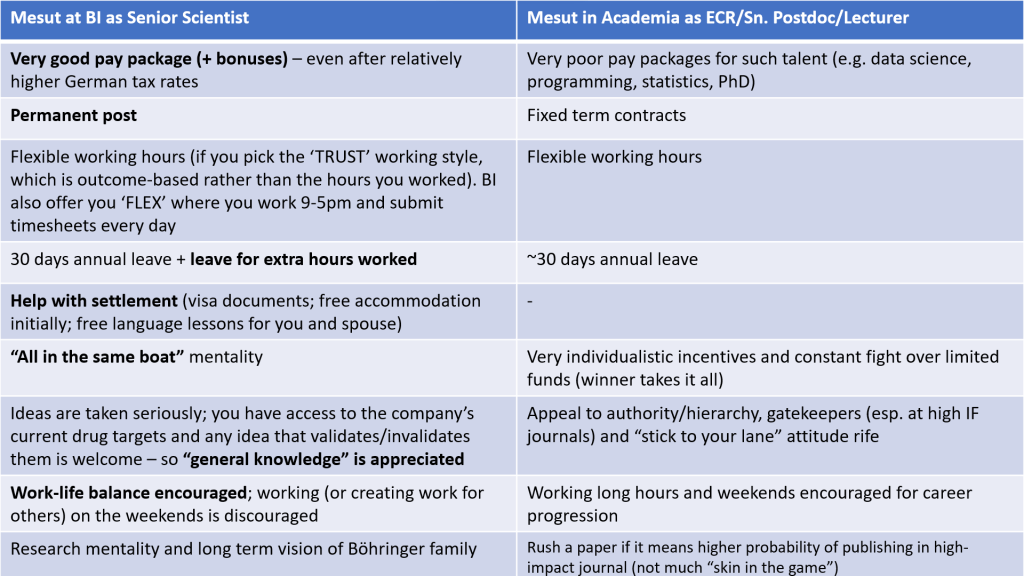

To get back to my views of ‘working for BI v in academia’, I’ve made a summary table below which compares my experience as a Senior Scientist in BI and my time as an ECR/(Sn.) Postdoc/(Prospective) Lecturer in UK academia. I’ve highlighted in bold where I think one side better was than the other for me.

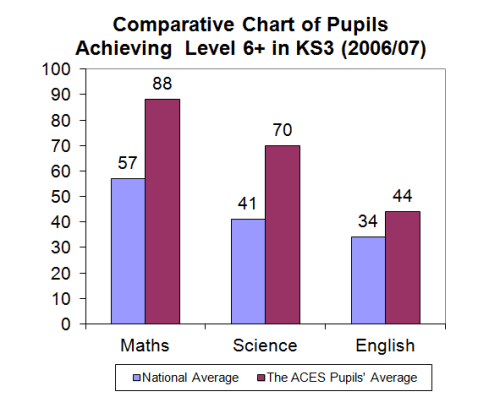

I also want to mention that career progression in UK academia is too slow for my liking (see below figure). I do not want to be treated as an ECR and living ‘paycheck to paycheck’ until I’m 50 – again, I feel like life is too short for this. This is why I wanted to move to a group where I would be respected more but also earning more – so that I can provide a good life for my family whilst fully concentrating on my/the team’s ‘cutting-edge’ research.

To finish, I again re-iterate that it would be wise for a talented postdoc with data science and statistical skills to have a look around while they’re still comfortable in their current post (i.e. still have >12 months contract). If you have experience working with clinical and genetic data, then Pharma and Biotech companies would also be very interested in you.

I hope this post is of help, but feel free to contact me if you have specific questions that are not answered here.

Addendum (23/12/23) – Reflecting on my first ~2.5 years at BI’s Human Genetics team:

Still happy. Family’s happy here. South Germany is very good for families: Very safe. My son’s kindergarten is great; Biberach and surrounding area is great. So much to see and learn.

Happy with the research I’m doing, things I’ve learned/learning, and my impact in the drug target development process at BI.

Also check out our preprint on structural variants – a valuable resource, openly shared with the research community (Note: I had encouraged Boris Noyvert to join our team and now we’ve published this preprint together):

Noyvert B, Erzurumluoglu AM, Drichel D, Omland S, Andlauer TFM et al. 2023. Imputation of structural variants using a multi-ancestry long-read sequencing panel enables identification of disease associations: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.12.20.23300308v1

Tweetorial: