This blog post first appeared on the Leicester Connect webpage (a platform for University of Leicester Alumni) on the 20th March 2020

Out of all the inspirational quotes on the internet, an old Sufi saying is the one that touches me the most:

“There are as many paths to God as there are souls on Earth.”

Although it is mostly used in a religious (mostly Islamic) setting, for me it carries truths that tower above this narrow meaning. It especially reminds me that we all start from different steps of the ladder, face different challenges along the way, and ultimately end up where we are because of the way we respond to those challenges, the doors that are open to us and the people we meet along the way – with the latter two we mostly cannot control.

I was kindly asked if I could write a blog post after being awarded the Future Leader Award at the 2020 Alumni Awards. I am grateful and honoured to have received the award but also acknowledge that there were at least two more people (my fellow finalists) who deserved it as much as me – if not more.

I would like to start by saying – from my experience in life and academia – that there are no objective criteria which separates those “who made it” versus those who just fell short. I got to meet plenty of people and interview panels who I felt judged me using very narrow and subjective criteria and ignored every other quality I had. It’s always nice to get the job or funding you applied for, however I never dwelled on the outcome if I did my preparation right. I would strongly recommend this approach.

Free yourself from the need for appreciation

Many academics suffer from a condition called Impostor Syndrome – simply put, doubting one’s own accomplishments and constantly fearing being exposed as a “fraud”. I can’t say I ever had it because I always thought of myself as successful in my own way and never sought confirmation from anyone. Although striving to improve myself all the time, I was happy with “just trying to do the right things” – irrespective of the outcome.

I base this belief on the fact that the people who judge us do not know the full story about us. Maybe if they did, they would look at us differently. For example, someone who is born to a middle-class English family will not be able to judge how much of a success it is for an immigrant to learn advanced-level English from scratch, get citizenship and compete for the same positions. Someone who has not had any serious health issues will not be able to comprehend what success is for a disabled person. How about a person who has managed to stay away from crime in a neighbourhood full of ignorance, hate and violence? None of these are mentioned in a CV and no one finds these people and offers them an MBE… or a job. However, this doesn’t change the fact that these people are inspirational and successful. I can only wish more people would realise this and stop treating subjective decisions about themselves or others as objective truths.

I feel privileged to be living in the UK which is a relatively meritocratic country and has a higher quality of life index compared to most. However, this also means that the competition is fiercer for “top jobs” and can mean those from underprivileged backgrounds are affected severely. One must realise this early on and respond to the challenge. The good news is that there are plenty of people out there who are willing to help and share their knowledge and experience when approached.

Believe in yourself but get help. Make friends!

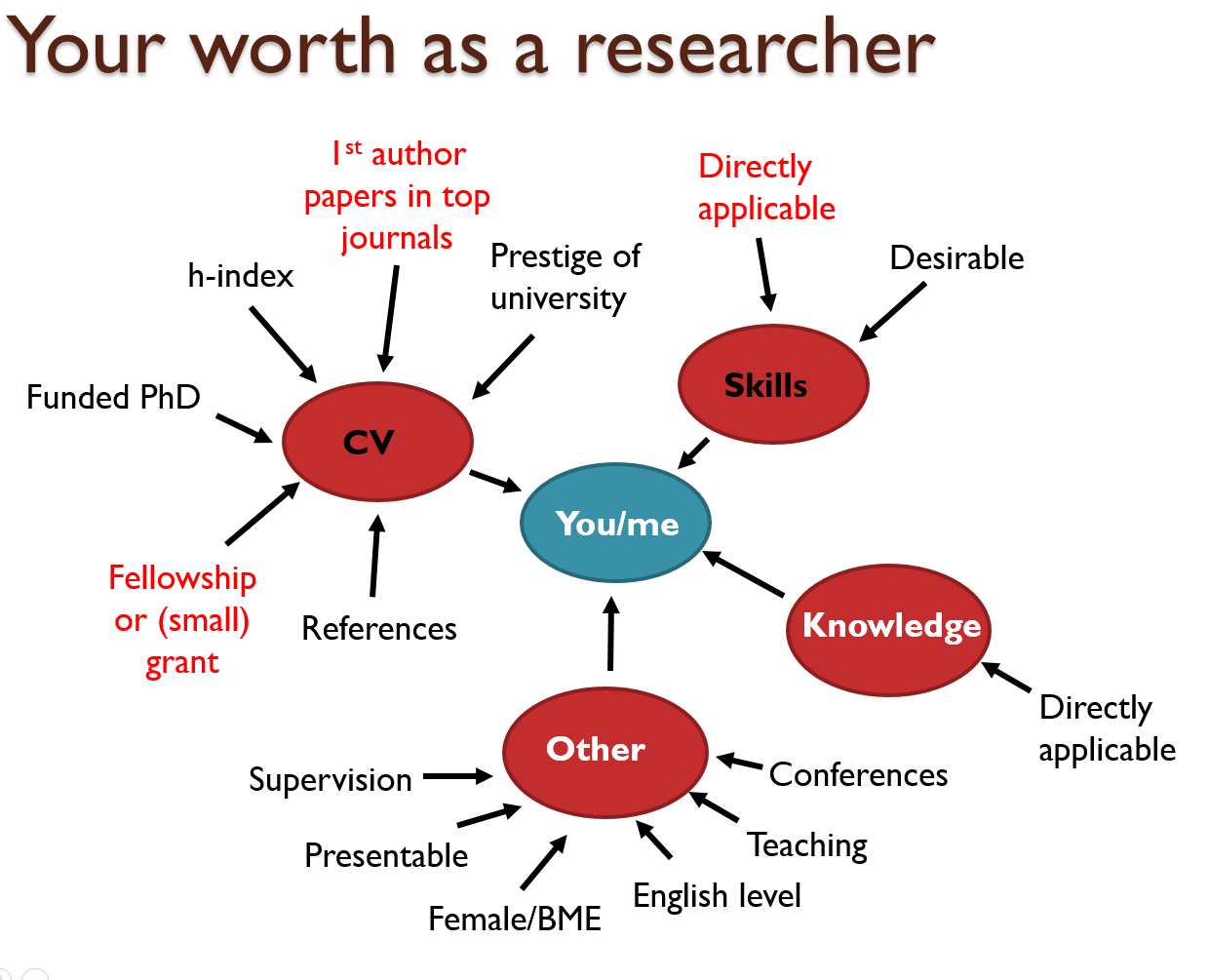

I had to overcome many financial, emotional and visa issues during my undergraduate years which undoubtedly affected my performance. When I somehow graduated from the University of Leicester with a 2.1 in BSc Genetics in 2011, I did not listen to the people who thought I would not be able to make the cut in academia and started applying for PhDs. Before applying, I read all the blogs and papers that were out there about “selling yourself well” and making your CV stand out. I always did my research before taking an important step. Thankfully, I must have been at the right place at the right time as I was very fortunate to be offered a fully-funded studentship at the University of Bristol – I remember even my interview not going that well. The scholarship freed me from the shackles of financial distress as I was embarking on an academic career.

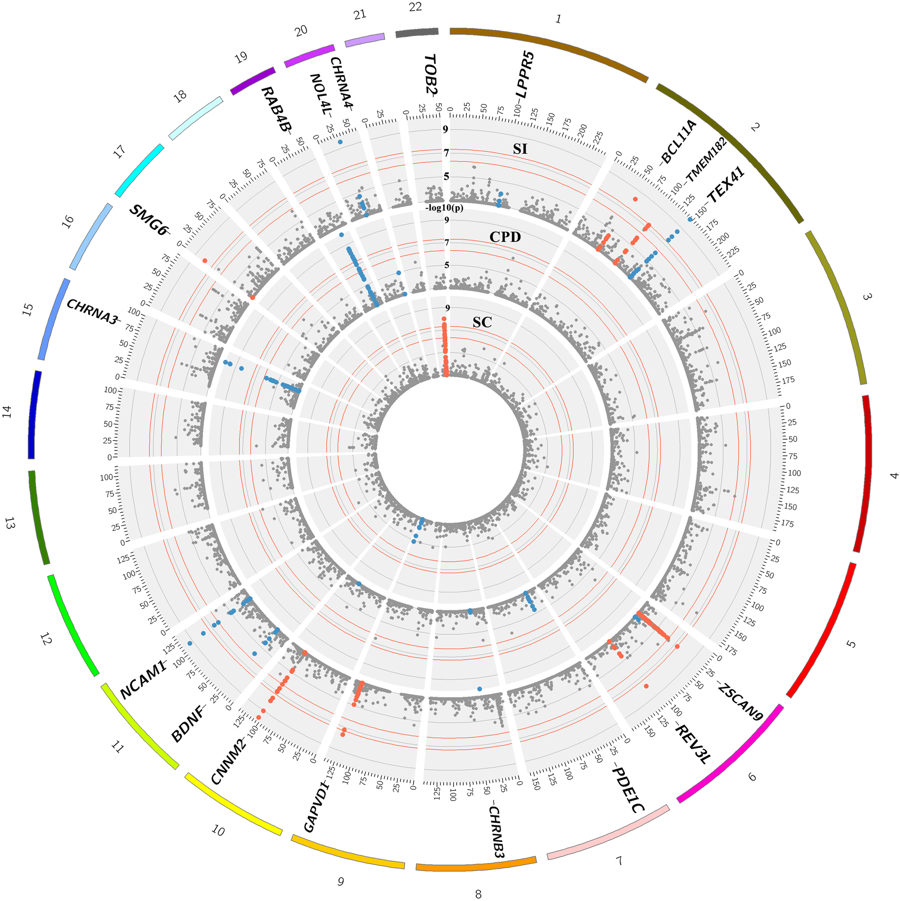

Again, doing my thorough background reading, I quickly realised that the field of Genetic Epidemiology – the field I now found myself in – required a solid foundation in medical statistics, epidemiology, bioinformatics, and programming as well as human genetics. I realised and accepted my limited expertise in these fields and got to work. I got all the help and knowledge I need from my supervisors, friends, online courses, blogs and research papers. I made sure I spent at least 2-3 hours a day on improving myself on top of working on my specific PhD project. Not keeping to myself, I was also supportive and sincere with my “PhD friends” who were on the same boat as me. I’m still close with many of my supervisors/teachers and friends. I couldn’t have achieved what I’ve achieved without their help.

Ultimate success: happiness and self-respect

In this fast-paced world, especially in academia, we continually forget that family and friends are worth more than any academic success. Although my academic papers are important to me – and I can only hope they’ll be useful to someone, somewhere, somehow – I do not spend much time thinking about my papers or PhD thesis. But I’m always longing to spend more time with my family and friends and the fact that I have them is the success of my life.

I want to finish by saying that I was very fortunate to get to where I am and achieve many milestones in the process, but it could have all turned out very differently, very easily. Yes, I tried to do the right things, but many things were out of my control. But as long as I had my friends and family, I’d like to think I would have been happy wherever I ended up.

I wrote all of these to convince you of one thing: do not let others – even senior people – define what success is for you as they do not know you and how you got to where you are. Just keep doing the rights things and, with the help and support of your loved ones, you’ll eventually get through everything in life.

Feel free to contact me!

I blog – in English and Turkish – about my research and other academia and culture-related things…

E.g. a post that may be of interest: An Academic Career in the UK

Download

If you’d like to download the blog post as it appeared on the Leicester Connect website, click the ‘Download’ button below: